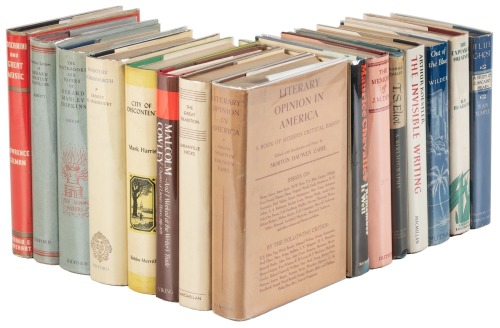

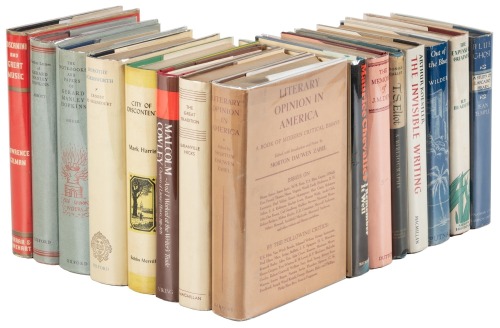

[Eliot, T.S.] — Gérard de Nerval Les Filles du Feu. Paris: Ernest Flammarion, [n.d., ca. 1904?]; [And:] La Vie Et L'Oeuvre. Paris: Alphonse Lemerre, 1906

Les Filles du Feu. 12mo. Half-title; browning and slight marginal chipping. Original cream pictorially printed wrappers, upper wrapper with ownership signature of T.S. Eliot ("Thomas Eliot 1909".); upper wrapper cleanly detached, vertical splits to spine, some chipping, text block split. — Gauthier Ferrieres. La Vie Et L'Oeuvre. 8vo. Half-title, frontispiece; marginal browning. Original yellow wrappers, upper wrapper with ownership signature of T.S. Eliot ("T.S. Eliot 1909.); upper wrapper detached, chipping, spine largely perished, text block split. Housed together in brown paper "expanding wallet" with string fasten, address label of the widow of Eliot's brother, Henry Ware Eliot Jnr ("Mrs. H.W. Eliot Jr. | 84 Prescott Street | Cambridge, Massachusetts") to flap, and second label ("Gerard de Nerval * T.S.E., 1909.") to top of wallet; short splits to folds.

Eliot's copy of Nerval's Les Filles du Feu, and Ferrieres' biography of the French poet.Works by and about the writer whose poetry influenced "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," The Waste Land, and Eliot's other verses.

Gérard de Nerval was the pen name of French Romantic writer, translator, and poet Gérard Labrunie. His 1828 translation of Goethe’s Faust was widely praised, but after a manic episode in 1841 Labrunie was given the diagnosis of insanity, and following an extended hospitalization he took the name Nerval. Around this time, Nerval gained a reputation for walking a pet lobster on a leash through the Palais Royal Gardens in Paris. "I have a liking for lobsters," he declared. "They are peaceful, serious creatures who know the secrets of the sea and don't bark" (Cavanaugh 108).

Through his experimental poetry and prose, Nerval explored the interstices of imagination and reality, creativity and madness. Cited as an influence by Marcel Proust André Breton and Antonin Artaud it was perhaps his impact on T.S. Eliot that proved most significant. Nerval's lines echo throughout Eliot's, often when the latter is exploring the liminal space between outer and inner lives, striving to convey the most nuanced of sentiments and emotions. In "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," for example, Eliot writes:

I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each.

I do not think that they will sing to me.

I have seen them riding seaward on the wavesCombing the white hair of the waves blown backWhen the wind blows the water white and black.We have lingered in the chambers of the sea... (124-129)

These now-iconic lines clearly draw upon those penned by Nerval in his "El Desdichado" ("The Disinherited," which appears in Les Filles du feu, present here): "J'ai rêvé dans la grotte où nage la sirène ... tour à tour" ("I have dreamed in the cave where the siren swims . . . one by one"). This parallelism occurs in the concluding stanzas of Eliot's early masterpiece, when Prufrock attempts to be subsumed into the fantasy of the "sea-girls" singing their songs. While these imaginings offer a welcome alternative to the chatter over teacups, and the women who come and go (talking of Michelangelo), such an escape is impossible. For, as Eliot writes in the final line of "Prufrock," "human voices wake us, and we drown." Interestingly, it is Nerval who defines these women as sirens through his verse, a term Eliot is careful to avoid in "Prufrock." Instead, Eliot subverts the traditional notion of the siren call, making the relentlessness of the everyday—restless nights in one-night cheap hotels, [a]nd sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells—the real threat.

The themes mentioned above come to constitute an essential vein running through the body of Eliot's work. Given this, it is perhaps only natural that Nerval would come to serve as a sort of touchstone for Eliot, the rhythm of his forbearer's words beating through his own. Indeed, the concluding stanza of The Waste Land —arguably the most important work of the Modernist movement—again borrows from Nerval, and here in even more direct fashion:

I sat upon the shoreFishing, with the arid plain behind meShall I at least set my lands in order?London Bridge is falling down falling down falling downPoi s’ascose nel foco che gli affinaQuando fiam uti chelidon—O swallow swallowLe Prince d’Aquitaine à la tour abolieThese fragments I have shored against my ruinsWhy then Ile fit you. Hieronymo’s mad againe.Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata. Shantih shantih shantih

Line 429, "Le Prince d’Aquitaine à la tour abolie," is again taken from Nerval's "El Desdichado," a work Eliot apparently turned to again and again:

Je suis le ténébreux,—le veuf,—l'inconsolé,Le prince 'Aquitaine à la tour abolie:Ma seule toile est morte, —et mon luth constelléPorte le soleil noir de la Mélancholie.

(I am the shadow, the widower, the unconsoled, the Aquitainian prince with the ruined tower: my only star is dead, and my star-strewn lute bears the black sun of Melancholy.)

Through his verse, Nerval laments the loss of the culture that troubadours were borne out of. In the poem, de Nerval's persona, the Prince of Aquitaine, feels disinherited from the tradition of the troubadours, and his sense of loss or threat is unmistakable. It is easy to map these themes onto The Waste Land—to understand how they speak to the anxiety Eliot conveys surrounding the decay of art, oral and written culture, civilization itself.

Eliot's appreciation for Nerval was apparently a constant in his life. Following a reading of Eliot's at Columbia University in April of 1958, Jacques Barzun, the French-born American historian wrote to the poet on 12 August, after "having gone over the recording several times," to enquire about his pronunciation,"prine' dAquitaine", making "eleven syllables instead of the twelve that a verse reading would require." Eliot replied to Barzun on the 5ht of September: "I was unaware of my elision of the mute e in the line from Nerval and think it could only have been due to unconscious assimilation of the French to the English context. I do think that to sound the mute e there would have given a somewhat precious and self-conscious effect and I am not altogether sorry that I missed it, but I must admit that it was unconscious" (Ricks and McCue 706). That Nerval would remain such an immediate presence is perhaps unsurprising. After all, like Tiresias in The Waste Land, they were both "throbbing between two lives."

A pair of exceptional association copies.

[Eliot, T.S.] — Gérard de Nerval Les Filles du Feu. Paris: Ernest Flammarion, [n.d., ca. 1904?]; [And:] La Vie Et L'Oeuvre. Paris: Alphonse Lemerre, 1906

Les Filles du Feu. 12mo. Half-title; browning and slight marginal chipping. Original cream pictorially printed wrappers, upper wrapper with ownership signature of T.S. Eliot ("Thomas Eliot 1909".); upper wrapper cleanly detached, vertical splits to spine, some chipping, text block split. — Gauthier Ferrieres. La Vie Et L'Oeuvre. 8vo. Half-title, frontispiece; marginal browning. Original yellow wrappers, upper wrapper with ownership signature of T.S. Eliot ("T.S. Eliot 1909.); upper wrapper detached, chipping, spine largely perished, text block split. Housed together in brown paper "expanding wallet" with string fasten, address label of the widow of Eliot's brother, Henry Ware Eliot Jnr ("Mrs. H.W. Eliot Jr. | 84 Prescott Street | Cambridge, Massachusetts") to flap, and second label ("Gerard de Nerval * T.S.E., 1909.") to top of wallet; short splits to folds.

Eliot's copy of Nerval's Les Filles du Feu, and Ferrieres' biography of the French poet.Works by and about the writer whose poetry influenced "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," The Waste Land, and Eliot's other verses.

Gérard de Nerval was the pen name of French Romantic writer, translator, and poet Gérard Labrunie. His 1828 translation of Goethe’s Faust was widely praised, but after a manic episode in 1841 Labrunie was given the diagnosis of insanity, and following an extended hospitalization he took the name Nerval. Around this time, Nerval gained a reputation for walking a pet lobster on a leash through the Palais Royal Gardens in Paris. "I have a liking for lobsters," he declared. "They are peaceful, serious creatures who know the secrets of the sea and don't bark" (Cavanaugh 108).

Through his experimental poetry and prose, Nerval explored the interstices of imagination and reality, creativity and madness. Cited as an influence by Marcel Proust André Breton and Antonin Artaud it was perhaps his impact on T.S. Eliot that proved most significant. Nerval's lines echo throughout Eliot's, often when the latter is exploring the liminal space between outer and inner lives, striving to convey the most nuanced of sentiments and emotions. In "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock," for example, Eliot writes:

I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each.

I do not think that they will sing to me.

I have seen them riding seaward on the wavesCombing the white hair of the waves blown backWhen the wind blows the water white and black.We have lingered in the chambers of the sea... (124-129)

These now-iconic lines clearly draw upon those penned by Nerval in his "El Desdichado" ("The Disinherited," which appears in Les Filles du feu, present here): "J'ai rêvé dans la grotte où nage la sirène ... tour à tour" ("I have dreamed in the cave where the siren swims . . . one by one"). This parallelism occurs in the concluding stanzas of Eliot's early masterpiece, when Prufrock attempts to be subsumed into the fantasy of the "sea-girls" singing their songs. While these imaginings offer a welcome alternative to the chatter over teacups, and the women who come and go (talking of Michelangelo), such an escape is impossible. For, as Eliot writes in the final line of "Prufrock," "human voices wake us, and we drown." Interestingly, it is Nerval who defines these women as sirens through his verse, a term Eliot is careful to avoid in "Prufrock." Instead, Eliot subverts the traditional notion of the siren call, making the relentlessness of the everyday—restless nights in one-night cheap hotels, [a]nd sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells—the real threat.

The themes mentioned above come to constitute an essential vein running through the body of Eliot's work. Given this, it is perhaps only natural that Nerval would come to serve as a sort of touchstone for Eliot, the rhythm of his forbearer's words beating through his own. Indeed, the concluding stanza of The Waste Land —arguably the most important work of the Modernist movement—again borrows from Nerval, and here in even more direct fashion:

I sat upon the shoreFishing, with the arid plain behind meShall I at least set my lands in order?London Bridge is falling down falling down falling downPoi s’ascose nel foco che gli affinaQuando fiam uti chelidon—O swallow swallowLe Prince d’Aquitaine à la tour abolieThese fragments I have shored against my ruinsWhy then Ile fit you. Hieronymo’s mad againe.Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata. Shantih shantih shantih

Line 429, "Le Prince d’Aquitaine à la tour abolie," is again taken from Nerval's "El Desdichado," a work Eliot apparently turned to again and again:

Je suis le ténébreux,—le veuf,—l'inconsolé,Le prince 'Aquitaine à la tour abolie:Ma seule toile est morte, —et mon luth constelléPorte le soleil noir de la Mélancholie.

(I am the shadow, the widower, the unconsoled, the Aquitainian prince with the ruined tower: my only star is dead, and my star-strewn lute bears the black sun of Melancholy.)

Through his verse, Nerval laments the loss of the culture that troubadours were borne out of. In the poem, de Nerval's persona, the Prince of Aquitaine, feels disinherited from the tradition of the troubadours, and his sense of loss or threat is unmistakable. It is easy to map these themes onto The Waste Land—to understand how they speak to the anxiety Eliot conveys surrounding the decay of art, oral and written culture, civilization itself.

Eliot's appreciation for Nerval was apparently a constant in his life. Following a reading of Eliot's at Columbia University in April of 1958, Jacques Barzun, the French-born American historian wrote to the poet on 12 August, after "having gone over the recording several times," to enquire about his pronunciation,"prine' dAquitaine", making "eleven syllables instead of the twelve that a verse reading would require." Eliot replied to Barzun on the 5ht of September: "I was unaware of my elision of the mute e in the line from Nerval and think it could only have been due to unconscious assimilation of the French to the English context. I do think that to sound the mute e there would have given a somewhat precious and self-conscious effect and I am not altogether sorry that I missed it, but I must admit that it was unconscious" (Ricks and McCue 706). That Nerval would remain such an immediate presence is perhaps unsurprising. After all, like Tiresias in The Waste Land, they were both "throbbing between two lives."

A pair of exceptional association copies.

Testen Sie LotSearch und seine Premium-Features 7 Tage - ohne Kosten!

Lassen Sie sich automatisch über neue Objekte in kommenden Auktionen benachrichtigen.

Suchauftrag anlegen