ERNST CHAIN'S NOBEL PRIZE FOR PENICILLINThe 1945 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, awarded to Sir Ernst Chain for his work on the discovery of penicillin:

Nobel Prize medal struck in 23 carat gold, approximately 200g., 67mm in diameter, design by Erik Lindberg and manufactured by the Swedish Royal Mint (Kungliga Mynt och Justeringsverkey);

the obverse with bust of Alfred Nobel facing left, "ALFR. / NOBEL" to left of bust, "NAT. / MDCCC / XXXIII / OB. / MDCCC / XCVI" to right of bust, signed "E. LINDBERG 1902" to the lower left edge;

the reverse featuring an allegorical vignette of the Genius of Medicine with an open book on her lap, collecting the water pouring from a rock to aid a sick girl beside her, the legend above reading "INVENTAS VITAM IUVAT EX COLUISSE PER ARTES", the plaque below the vignette reading "E.B. CHAIN / MCMXLV", the motto to either side of the plaque reading "REG. UNIVERSITAS" "MED. CHIR. CAROL.", signed "E. LINDBERG" to the lower right of the vignette,

housed in the original diced maroon morocco case with gilt decoration, lined in velvet and satin,

TOGETHER WITH:

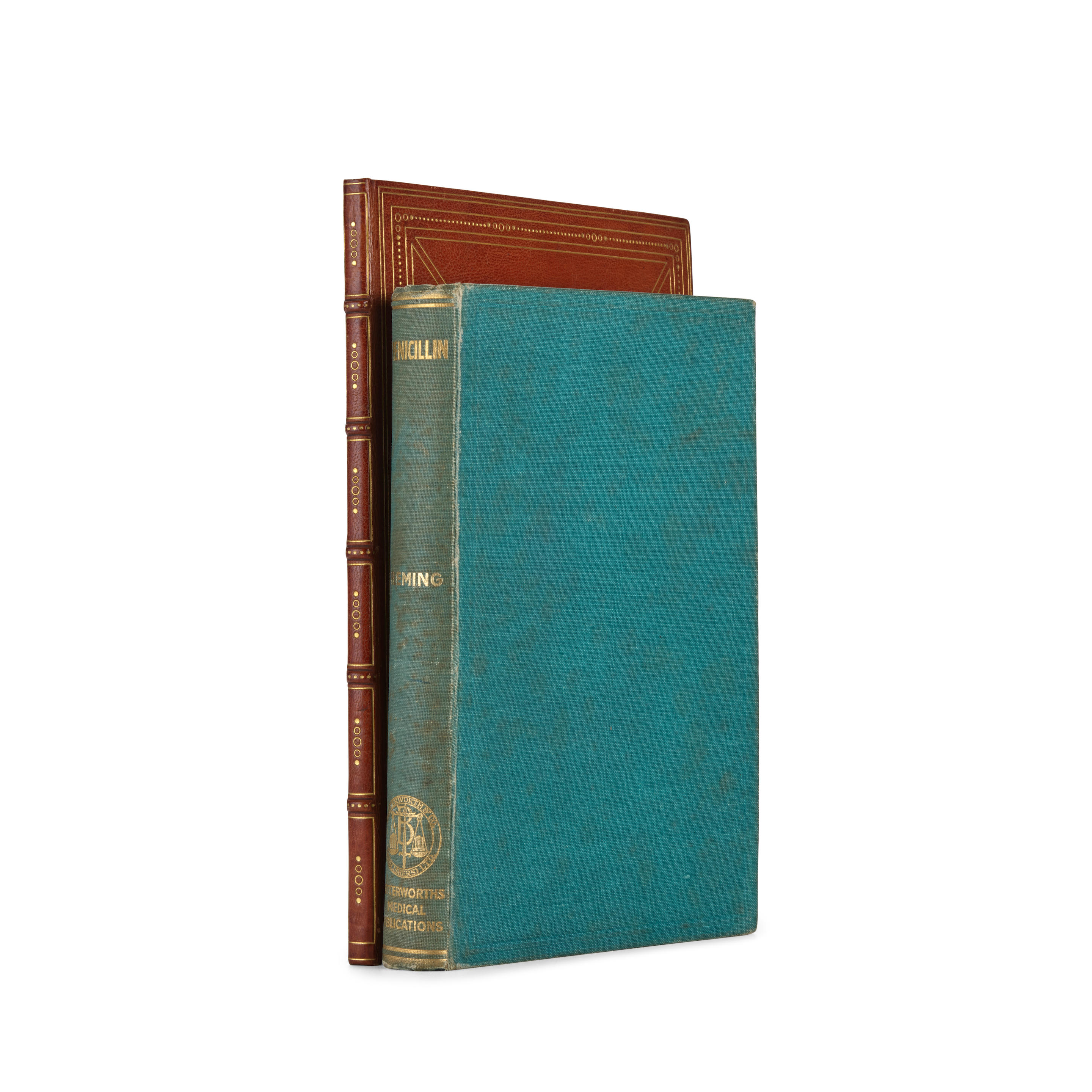

(i) Nobel Prize Diploma presented to Sir Alexander Fleming, Ernst Boris Chain, and Sir Howard Walter Florey, issued jointly 'for the discovery of penicillin and its curative effect in various infectious diseases', the first leaf featuring a unique artwork by the Swedish artist Jerk Werkmäster (1896-1978), depicting two figures in front of a tree with a central cartouche bearing the initials "EBC"; one figure wears a suit of armour and carries a flag emblazoned with three crowns, the national emblem of Sweden; the second figure wears a lab coat and carries a flag emblazoned with the bowl of Hygeia, the rod of Asclepius, and a rooster (sacred bird to Asclepius); the second leaf with calligraphic inscription in Swedish in blue, black and red, signed beneath by 28 members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Science, 2 leaves, on vellum, each 341 x 242mm., mounted in a blue leather gilt-ruled portfolio, upper cover with gilt-stamped central wreath encircling the monogram "EBC" [Ernst Boris Chain], lower cover with gilt-stamped staff of Asclepius, Stockholm, 25th October 1945.

(ii) Typescript of Ernst Chain's Nobel Prize acceptance speech ( '...As a member of one of the most cruelly persecuted races in the world I am profoundly grateful to Providence that it has fallen to me, together with my friend Sir Howard Florey, to originate this work on penicillin which has helped to alleviate the suffering of the wounded soldiers of Britain, the country that has adopted me...') 3 pages, rectos only, (225 x 360mm.), with carbon copy, and a later printed copy of the speech.Footnotes'THE HIGHEST DISTINCTION A SCIENTIST MAY HOPE TO ACHIEVE': THE NOBEL MEDAL AWARDED TO SIR ERNST CHAIN FOR HIS WORK ON THE DISCOVERY OF PENICILLIN.

In the Nobel presentation speech by Professor G. Liljestrand, he celebrates the work of Ernst Chain, Howard Florey, and Alexander Fleming:

"in a time when annihilation and destruction through the inventions of man have been greater than ever before in history, the introduction of penicillin is a brilliant demonstration that human genius is just as well able to save life and combat disease."

The discovery of penicillin, and its curative effect in infectious diseases, is arguably the most profoundly important discovery in the field of medical science in the 20th century. More than 200 million lives are estimated to have been directly saved by the use of penicillin as an anti-bacterial treatment. Previously fatal ailments were easily treatable as a result of this research. The Nobel Prize is recognised internationally as the highest possible accolade in the field of Physiology or Medicine, and the present lot is the prize awarded to Doctor Ernst Chain for his central role in this world-changing discovery.

The Prelude To Chain's Nobel Prize-winning Contribution To Penicillin

The quest to counteract infectious diseases made significant progress as early as the 19th century, with the valuable research work by Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch. With the nature of such diseases identified and linked to the invasion of bacteria, attempts at developing vaccinations and treatments accelerated. For antibiotics, one of the earliest forays was the experiments of Lord Lister in 1871, which – though inconclusive – explored the possibility of the growth of a fungus creating a less favourable environment for bacteria. A year later, William Roberts of the Manchester Victoria hospital noted antagonism between fungi and bacteria. In 1876, separate research by John Tyndall also noted the combative effect of Penicillium glaucum on bacterial micro-organisms. New methods of application were also discovered and developed around this time, as shown by the awarding of the first ever Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1901 to Emil von Behring for his work on serum therapy.

It is against this backdrop of intense medical development that Alexander Fleming observed the effectiveness of a rarer, contaminated mould he described as Penicillium notatum prevented the growth of bacteria from the staphylococcus group. The substance itself he named penicillin, which prevented the formation of new bacterial cell walls, resulting in the slowing of reproduction, and eventual death of, the targeted bacteria. After Fleming published his observations in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology (No. 10, 1929), and with early attempts to purify the mould by Clutterbuck, Lovell and Raistrick ending in limited success, research into penicillin appears to have paused indefinitely. It was not until 1939 and the work of the William Dunn School of Pathology at Oxford University – headed by Sir Howard Florey and with the defining contributions of Ernst Chain – that the extent of its curative effects could be realized:

"The introduction of penicillin into clinical medicine... [was] of a magnitude such as no-one could possibly foresee... even in the loftiest flights of fantasy"

Ernst Chain ('25 Years Of Penicillin', draft manuscript)

Ernst Chain's Early Life And Career

Born in Berlin in 1906, Ernst Boris Chain was from a diverse continental background; his mother (Margaret Eisner) was German, his father (Michael Chain) Russian, both of Jewish origin. Chain developed an interest in chemistry from a young age, inspired by his father's occupation as a trained chemist. He obtained his degree from the Friedrich-Wilhelm University in Berlin in 1930. His other great passion was music, and as a skilled pianist and music critic in the 1920s his future may have been in the arts rather than science (Chain continued to perform recitals throughout his academic career).

Despite Chain's talents and ambitions, he was forced to leave Germany in 1933. The appointment of Hitler as German Chancellor was swiftly followed by restrictive measures limiting the rights of Jewish citizens including access to universities. Amidst increasing anti-Semitism in his home country, and threatened with the loss of rights and research opportunities, Chain made the difficult decision to emigrate to the United Kingdom, receiving his first doctorate in absentia; his mother and sister stayed in Germany, and died during the Holocaust. Chain was unable to obtain his British certificate of naturalization until the 18th April 1939.

On moving to England, Ernst Chain briefly worked at University College London, in the laboratories of the renowned Professor C.R. Harrington. Between 1933 and 1935 he researched at the University of Cambridge and obtained his second doctorate.

By 1935 Chain had transferred to Oxford University to work with Professor Howard Florey, who had recently been appointed the head of the William Dunn School of Pathology. In their earliest known correspondence, Florey invites him to a quick lunch which 'I must leave soon after that' – a brief encounter which led to one of the most important scientific partnerships in 20th century medicine. His early Oxford years focused on diverse subjects including snake venom, tumour metabolism, and lysozyme action (by chance the latter subject, like penicillin, had first been described by Alexander Fleming). However, it was in 1939 that Chain and Florey began their systematic study of antibacterial substances, which included the re-investigation of penicillin and the development of its application in humans. Fleming was not involved in this project, and was not contacted by Chain for some years – so much time had elapsed since the 1929 publication that he assumed that Fleming may have either retired or passed away.

"Mr Penicillin" – Ernst Chain and the discovery of Penicillin

After a series of preliminary experiments, Ernst Chain was directly responsible for developing the system of producing penicillin mould in vast quantities, for the purpose of isolating and purifying the organic material. Soon after, Chain discovered that the mould activity could be extracted into concentrated methyl alcohol, of which up to 40mg would be non-toxic to the mice used in live experiments.

Howard Florey then tested this substance in May 1940 on eight infected mice – all four specimens supplied with the penicillin sample survived, while the four without died in less than 24 hours. Chain described the result of this particular experiment at the time as "clear-cut", and it formed the basis of Chain and Florey's future experiments on penicillin. In order to increase the capacity of the project, additional members (including N.G. Heatley and E.P. Abraham) and resources were made available, referred to by the Nobel committee as 'The Oxford Unit'. Once the penicillin samples could be purified to the extent that intravenous application to man was 'without ill effects', in Chain's words 'with this preparation the biological properties of penicillin (and its chemotherapeutic value in severe bacterial infections in man) was developed'.

The Second World War had been raging throughout this project, and the immediate applications of penicillin – once ready – were all too clear, something Chain alluded to in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech. By February 1941 the first human had been treated with penicillin, and two years later both Chain and Florey visited North Africa to oversee the treating of wounded Allied soldiers with penicillin. Chain would later petition for there to be no monopoly or patent for penicillin production, having seen its curative effects on so many patients already. By the time of the Normandy landing in June 1944, the production of penicillin had been vastly improved and is seen as an important factor in reducing casualties during this period of the conflict. An advertisement in an issue of Life magazine from 14th August 1944 emphatically proclaimed "Thanks to penicillin... He will come home!".

Ernst Chain's storied career continued at Oxford, and later in Rome and London (Imperial College) until his passing in 1979, but it was for his role in the development of penicillin which saw him awarded the Nobel Prize in 1945. In his own words, Chain succinctly defined his and Florey's central roles in the story of penicillin:

"The distribution of the work was that E.C (Ernst Chain) was to produce antibacterial material from Penicillium notatum in a form suitable for injection into animals, and H.W.F. (Howard Florey) was to investigate the biological properties of such material and its therapeutic potentialities."

The Enduring Legacy Of Penicillin

Hailed at the time as the supreme antibiotic, the curative effect of penicillin was by no means restricted to cuts and wounds with bacterial infections. Meningitis, syphilis, gonorrhoea, throat infections, and a host of other bacterial infections could be treated as a result, which would otherwise have remained debilitating or life-threatening ailments. Further developments have improved its effectiveness further still, including Ernst Chain's own work in Rome during the 1950s on developing a semi-synthetic penicillin. Over 80 years since the first clinical use of penicillin, global health has significantly changed for the better, thanks in large part to the ability, determination, and dedication of Sir Ernst Chain.

The Nobel Prize

On the 25th October 1945, a telegram was sent to Ernst Chain by rector Hilding Bergstrand of the Caroline Institute (the selecting body for this Nobel Prize):

"Doctor Ernst Boris Chain, Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, Oxford:

The Caroline Institute has decided to award this year's Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine to you, Professor Fleming and Professor Florey jointly, for the discovery of penicillin and its curative action in various infectious diseases."

Chain was working in America at the time the telegram was sent, so he was unable to respond until almost a month later. Only a fortnight before the Nobel Prize ceremony was scheduled to take place, he replied:

"The award to me of a Nobel Prize... is indeed a very great honour and I should like to express my sincere thanks for, and my deep appreciation of the impartial judgment displayed by the Nobel Committee and the Caroline Institute."

The Nobel prizegiving ceremony itself took place on the 10th December 1945, in the Main Hall of Stockholm's Konserthuset. At 5 o'clock sharp, with the Nobel laureates and guests in attendance, King Gustav V of Sweden began proceedings by entering the hall to trumpet blasts and the royal hymn. Chain and the other Nobel laureates then processed to the stage together with past Nobel Prize winners and the proposing committee members for the 1945 Prizes. Ernst Chain was flanked by Sir Alexander Fleming and Sir Howard Florey, and accompanied by Folke Henschen, professor of pathological anatomy at the Caroline Institute. Following a short speech in Swedish by Professor Liljestrand – who was the first to inform Chain of his award – Chain received the present Nobel Prize medal and diploma directly from King Gustav.

During the following banquet held at the Royal Palace of Stockholm, Chain made the acceptance speech included in the present lot, which was viewed by the press at the time as 'by far the most arresting' of any speech that night. Ironically the speech could contain no actual detail on the chemical structure of penicillin; since 1943 the British and American governments had imposed a security ban, which would remain in place until early 1946. Nevertheless, Chain was deeply aware that the Second World War had ended only recently, and was determined to champion medical science as a transformative power going forward. He described his contribution as a means "to alleviate some of the suffering that this most terrible of all wars has inflicted on mankind, and which will continue to benefit humanity during the period of peace that lies ahead". Where politicians had failed in the first half of the 20th century, Chain proposed science as the key means of improving society, but with a warning for the future ("...unless we do succeed in building up a social structure which enables us to keep pace with and control over the scientific advances we shall irretrievably and completely lose all that civilisation which has been our heritage...The construction of such an international society cannot be achieved by mere formulae elaborated by diplomatists... it can only come through the full realisation of the common man and woman that they are in imminent mortal danger if control is lost of the scientific creation, but that on the other hand vast and unparalleled opportunities are open to them..."). Indeed, penicillin was, and continues to be, a sign of that most noble of endeavours.

Provenance: Sir Ernst Chain (1906-1979); thence by direct descent to the present owners.Read MoreAdditional informationAuction informationBuyers Premium and ChargesFor all Sales categories, buyer's premium excluding Cars, Motorbikes, Wine, Whisky and Coin & Medal sales, will be as follows:Buyer's Premium Rates

28% on the first £40,000 of the hammer price;

27% of the hammer price of amounts in excess of £40,000 up to and including £800,000;

21% of the hammer price of amounts in excess of £800,000 up to and including £4,500,000;

and 14.5% of the hammer price of any amounts in excess of £4,500,000.VAT at the current rate of 20% will be added to the Buyer's Premium and charges excluding Artists Resale Right.Buyers' ObligationsALL BIDDERS MUST AGREE THAT THEY HAVE READ AND UNDERSTOOD BONHAMS' CONDITIONS OF SALE AND AGREE TO BE BOUND BY THEM, AND AGREE TO PAY THE BUYER'S PREMIUM AND ANY OTHER CHARGES MENTIONED IN THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS. THIS AFFECTS THE BIDDERS LEGAL RIGHTS.If you have any complaints or questions about the Conditions of Sale, please contact your nearest customer services team.Payment NoticesFor payment information please refer to the sale catalog.Shipping NoticesFor information and estimates on domestic and international shipping as well as export licences please contact Bonhams Shipping Department.Related DepartmentsBooks & ManuscriptsAuction ViewingsLondon, Knightsbridge18 June 2023, 11:00 - 15:00 BST19 June 2023, 09:00 - 17:00 BST20 June 2023, 09:00 - 17:00 BST21 June 2023, 09:00 - 10:00 BSTConditions of SaleView Conditions of Sale

ERNST CHAIN'S NOBEL PRIZE FOR PENICILLINThe 1945 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, awarded to Sir Ernst Chain for his work on the discovery of penicillin:

Nobel Prize medal struck in 23 carat gold, approximately 200g., 67mm in diameter, design by Erik Lindberg and manufactured by the Swedish Royal Mint (Kungliga Mynt och Justeringsverkey);

the obverse with bust of Alfred Nobel facing left, "ALFR. / NOBEL" to left of bust, "NAT. / MDCCC / XXXIII / OB. / MDCCC / XCVI" to right of bust, signed "E. LINDBERG 1902" to the lower left edge;

the reverse featuring an allegorical vignette of the Genius of Medicine with an open book on her lap, collecting the water pouring from a rock to aid a sick girl beside her, the legend above reading "INVENTAS VITAM IUVAT EX COLUISSE PER ARTES", the plaque below the vignette reading "E.B. CHAIN / MCMXLV", the motto to either side of the plaque reading "REG. UNIVERSITAS" "MED. CHIR. CAROL.", signed "E. LINDBERG" to the lower right of the vignette,

housed in the original diced maroon morocco case with gilt decoration, lined in velvet and satin,

TOGETHER WITH:

(i) Nobel Prize Diploma presented to Sir Alexander Fleming, Ernst Boris Chain, and Sir Howard Walter Florey, issued jointly 'for the discovery of penicillin and its curative effect in various infectious diseases', the first leaf featuring a unique artwork by the Swedish artist Jerk Werkmäster (1896-1978), depicting two figures in front of a tree with a central cartouche bearing the initials "EBC"; one figure wears a suit of armour and carries a flag emblazoned with three crowns, the national emblem of Sweden; the second figure wears a lab coat and carries a flag emblazoned with the bowl of Hygeia, the rod of Asclepius, and a rooster (sacred bird to Asclepius); the second leaf with calligraphic inscription in Swedish in blue, black and red, signed beneath by 28 members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Science, 2 leaves, on vellum, each 341 x 242mm., mounted in a blue leather gilt-ruled portfolio, upper cover with gilt-stamped central wreath encircling the monogram "EBC" [Ernst Boris Chain], lower cover with gilt-stamped staff of Asclepius, Stockholm, 25th October 1945.

(ii) Typescript of Ernst Chain's Nobel Prize acceptance speech ( '...As a member of one of the most cruelly persecuted races in the world I am profoundly grateful to Providence that it has fallen to me, together with my friend Sir Howard Florey, to originate this work on penicillin which has helped to alleviate the suffering of the wounded soldiers of Britain, the country that has adopted me...') 3 pages, rectos only, (225 x 360mm.), with carbon copy, and a later printed copy of the speech.Footnotes'THE HIGHEST DISTINCTION A SCIENTIST MAY HOPE TO ACHIEVE': THE NOBEL MEDAL AWARDED TO SIR ERNST CHAIN FOR HIS WORK ON THE DISCOVERY OF PENICILLIN.

In the Nobel presentation speech by Professor G. Liljestrand, he celebrates the work of Ernst Chain, Howard Florey, and Alexander Fleming:

"in a time when annihilation and destruction through the inventions of man have been greater than ever before in history, the introduction of penicillin is a brilliant demonstration that human genius is just as well able to save life and combat disease."

The discovery of penicillin, and its curative effect in infectious diseases, is arguably the most profoundly important discovery in the field of medical science in the 20th century. More than 200 million lives are estimated to have been directly saved by the use of penicillin as an anti-bacterial treatment. Previously fatal ailments were easily treatable as a result of this research. The Nobel Prize is recognised internationally as the highest possible accolade in the field of Physiology or Medicine, and the present lot is the prize awarded to Doctor Ernst Chain for his central role in this world-changing discovery.

The Prelude To Chain's Nobel Prize-winning Contribution To Penicillin

The quest to counteract infectious diseases made significant progress as early as the 19th century, with the valuable research work by Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch. With the nature of such diseases identified and linked to the invasion of bacteria, attempts at developing vaccinations and treatments accelerated. For antibiotics, one of the earliest forays was the experiments of Lord Lister in 1871, which – though inconclusive – explored the possibility of the growth of a fungus creating a less favourable environment for bacteria. A year later, William Roberts of the Manchester Victoria hospital noted antagonism between fungi and bacteria. In 1876, separate research by John Tyndall also noted the combative effect of Penicillium glaucum on bacterial micro-organisms. New methods of application were also discovered and developed around this time, as shown by the awarding of the first ever Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1901 to Emil von Behring for his work on serum therapy.

It is against this backdrop of intense medical development that Alexander Fleming observed the effectiveness of a rarer, contaminated mould he described as Penicillium notatum prevented the growth of bacteria from the staphylococcus group. The substance itself he named penicillin, which prevented the formation of new bacterial cell walls, resulting in the slowing of reproduction, and eventual death of, the targeted bacteria. After Fleming published his observations in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology (No. 10, 1929), and with early attempts to purify the mould by Clutterbuck, Lovell and Raistrick ending in limited success, research into penicillin appears to have paused indefinitely. It was not until 1939 and the work of the William Dunn School of Pathology at Oxford University – headed by Sir Howard Florey and with the defining contributions of Ernst Chain – that the extent of its curative effects could be realized:

"The introduction of penicillin into clinical medicine... [was] of a magnitude such as no-one could possibly foresee... even in the loftiest flights of fantasy"

Ernst Chain ('25 Years Of Penicillin', draft manuscript)

Ernst Chain's Early Life And Career

Born in Berlin in 1906, Ernst Boris Chain was from a diverse continental background; his mother (Margaret Eisner) was German, his father (Michael Chain) Russian, both of Jewish origin. Chain developed an interest in chemistry from a young age, inspired by his father's occupation as a trained chemist. He obtained his degree from the Friedrich-Wilhelm University in Berlin in 1930. His other great passion was music, and as a skilled pianist and music critic in the 1920s his future may have been in the arts rather than science (Chain continued to perform recitals throughout his academic career).

Despite Chain's talents and ambitions, he was forced to leave Germany in 1933. The appointment of Hitler as German Chancellor was swiftly followed by restrictive measures limiting the rights of Jewish citizens including access to universities. Amidst increasing anti-Semitism in his home country, and threatened with the loss of rights and research opportunities, Chain made the difficult decision to emigrate to the United Kingdom, receiving his first doctorate in absentia; his mother and sister stayed in Germany, and died during the Holocaust. Chain was unable to obtain his British certificate of naturalization until the 18th April 1939.

On moving to England, Ernst Chain briefly worked at University College London, in the laboratories of the renowned Professor C.R. Harrington. Between 1933 and 1935 he researched at the University of Cambridge and obtained his second doctorate.

By 1935 Chain had transferred to Oxford University to work with Professor Howard Florey, who had recently been appointed the head of the William Dunn School of Pathology. In their earliest known correspondence, Florey invites him to a quick lunch which 'I must leave soon after that' – a brief encounter which led to one of the most important scientific partnerships in 20th century medicine. His early Oxford years focused on diverse subjects including snake venom, tumour metabolism, and lysozyme action (by chance the latter subject, like penicillin, had first been described by Alexander Fleming). However, it was in 1939 that Chain and Florey began their systematic study of antibacterial substances, which included the re-investigation of penicillin and the development of its application in humans. Fleming was not involved in this project, and was not contacted by Chain for some years – so much time had elapsed since the 1929 publication that he assumed that Fleming may have either retired or passed away.

"Mr Penicillin" – Ernst Chain and the discovery of Penicillin

After a series of preliminary experiments, Ernst Chain was directly responsible for developing the system of producing penicillin mould in vast quantities, for the purpose of isolating and purifying the organic material. Soon after, Chain discovered that the mould activity could be extracted into concentrated methyl alcohol, of which up to 40mg would be non-toxic to the mice used in live experiments.

Howard Florey then tested this substance in May 1940 on eight infected mice – all four specimens supplied with the penicillin sample survived, while the four without died in less than 24 hours. Chain described the result of this particular experiment at the time as "clear-cut", and it formed the basis of Chain and Florey's future experiments on penicillin. In order to increase the capacity of the project, additional members (including N.G. Heatley and E.P. Abraham) and resources were made available, referred to by the Nobel committee as 'The Oxford Unit'. Once the penicillin samples could be purified to the extent that intravenous application to man was 'without ill effects', in Chain's words 'with this preparation the biological properties of penicillin (and its chemotherapeutic value in severe bacterial infections in man) was developed'.

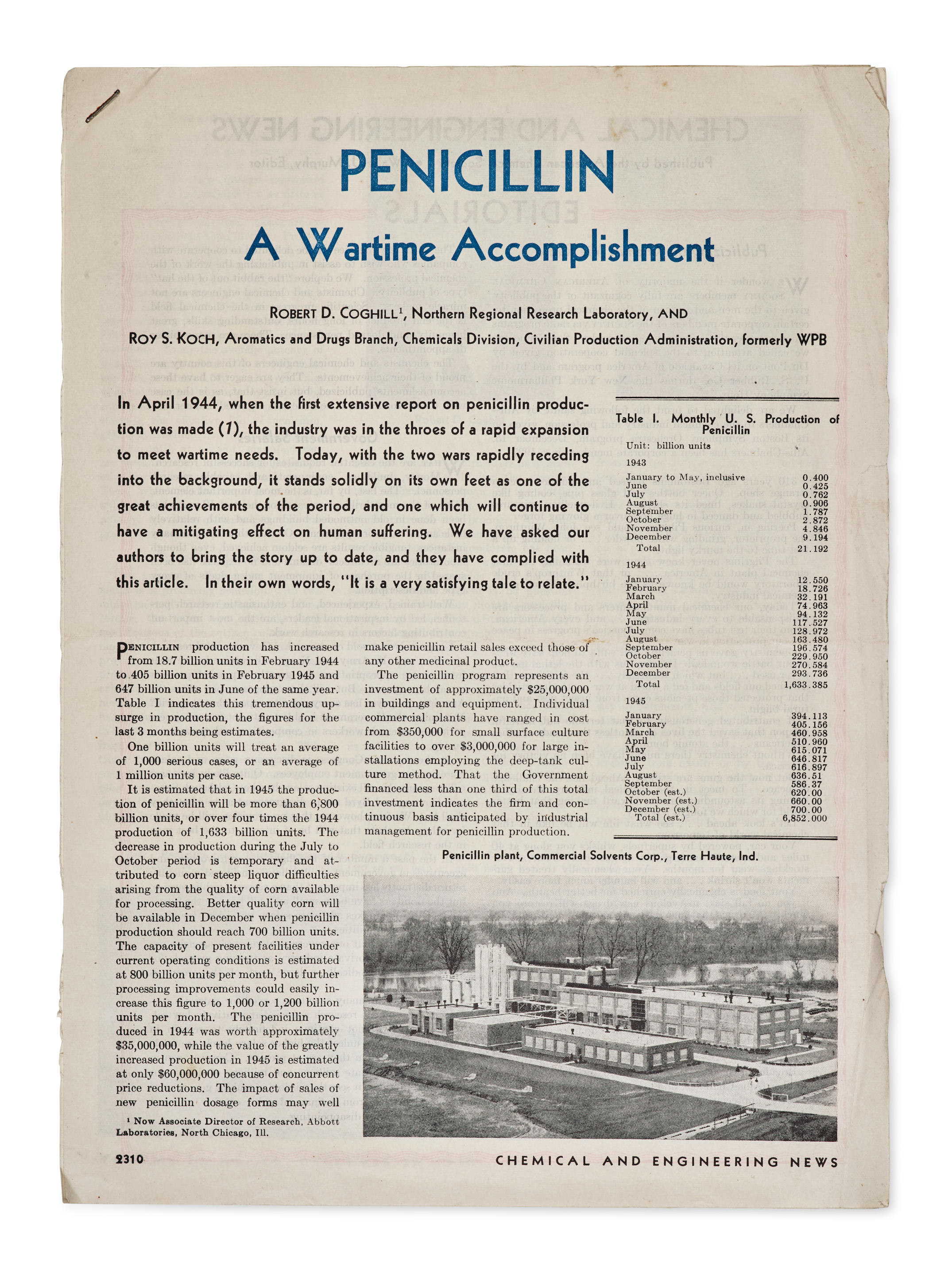

The Second World War had been raging throughout this project, and the immediate applications of penicillin – once ready – were all too clear, something Chain alluded to in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech. By February 1941 the first human had been treated with penicillin, and two years later both Chain and Florey visited North Africa to oversee the treating of wounded Allied soldiers with penicillin. Chain would later petition for there to be no monopoly or patent for penicillin production, having seen its curative effects on so many patients already. By the time of the Normandy landing in June 1944, the production of penicillin had been vastly improved and is seen as an important factor in reducing casualties during this period of the conflict. An advertisement in an issue of Life magazine from 14th August 1944 emphatically proclaimed "Thanks to penicillin... He will come home!".

Ernst Chain's storied career continued at Oxford, and later in Rome and London (Imperial College) until his passing in 1979, but it was for his role in the development of penicillin which saw him awarded the Nobel Prize in 1945. In his own words, Chain succinctly defined his and Florey's central roles in the story of penicillin:

"The distribution of the work was that E.C (Ernst Chain) was to produce antibacterial material from Penicillium notatum in a form suitable for injection into animals, and H.W.F. (Howard Florey) was to investigate the biological properties of such material and its therapeutic potentialities."

The Enduring Legacy Of Penicillin

Hailed at the time as the supreme antibiotic, the curative effect of penicillin was by no means restricted to cuts and wounds with bacterial infections. Meningitis, syphilis, gonorrhoea, throat infections, and a host of other bacterial infections could be treated as a result, which would otherwise have remained debilitating or life-threatening ailments. Further developments have improved its effectiveness further still, including Ernst Chain's own work in Rome during the 1950s on developing a semi-synthetic penicillin. Over 80 years since the first clinical use of penicillin, global health has significantly changed for the better, thanks in large part to the ability, determination, and dedication of Sir Ernst Chain.

The Nobel Prize

On the 25th October 1945, a telegram was sent to Ernst Chain by rector Hilding Bergstrand of the Caroline Institute (the selecting body for this Nobel Prize):

"Doctor Ernst Boris Chain, Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, Oxford:

The Caroline Institute has decided to award this year's Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine to you, Professor Fleming and Professor Florey jointly, for the discovery of penicillin and its curative action in various infectious diseases."

Chain was working in America at the time the telegram was sent, so he was unable to respond until almost a month later. Only a fortnight before the Nobel Prize ceremony was scheduled to take place, he replied:

"The award to me of a Nobel Prize... is indeed a very great honour and I should like to express my sincere thanks for, and my deep appreciation of the impartial judgment displayed by the Nobel Committee and the Caroline Institute."

The Nobel prizegiving ceremony itself took place on the 10th December 1945, in the Main Hall of Stockholm's Konserthuset. At 5 o'clock sharp, with the Nobel laureates and guests in attendance, King Gustav V of Sweden began proceedings by entering the hall to trumpet blasts and the royal hymn. Chain and the other Nobel laureates then processed to the stage together with past Nobel Prize winners and the proposing committee members for the 1945 Prizes. Ernst Chain was flanked by Sir Alexander Fleming and Sir Howard Florey, and accompanied by Folke Henschen, professor of pathological anatomy at the Caroline Institute. Following a short speech in Swedish by Professor Liljestrand – who was the first to inform Chain of his award – Chain received the present Nobel Prize medal and diploma directly from King Gustav.

During the following banquet held at the Royal Palace of Stockholm, Chain made the acceptance speech included in the present lot, which was viewed by the press at the time as 'by far the most arresting' of any speech that night. Ironically the speech could contain no actual detail on the chemical structure of penicillin; since 1943 the British and American governments had imposed a security ban, which would remain in place until early 1946. Nevertheless, Chain was deeply aware that the Second World War had ended only recently, and was determined to champion medical science as a transformative power going forward. He described his contribution as a means "to alleviate some of the suffering that this most terrible of all wars has inflicted on mankind, and which will continue to benefit humanity during the period of peace that lies ahead". Where politicians had failed in the first half of the 20th century, Chain proposed science as the key means of improving society, but with a warning for the future ("...unless we do succeed in building up a social structure which enables us to keep pace with and control over the scientific advances we shall irretrievably and completely lose all that civilisation which has been our heritage...The construction of such an international society cannot be achieved by mere formulae elaborated by diplomatists... it can only come through the full realisation of the common man and woman that they are in imminent mortal danger if control is lost of the scientific creation, but that on the other hand vast and unparalleled opportunities are open to them..."). Indeed, penicillin was, and continues to be, a sign of that most noble of endeavours.

Provenance: Sir Ernst Chain (1906-1979); thence by direct descent to the present owners.Read MoreAdditional informationAuction informationBuyers Premium and ChargesFor all Sales categories, buyer's premium excluding Cars, Motorbikes, Wine, Whisky and Coin & Medal sales, will be as follows:Buyer's Premium Rates

28% on the first £40,000 of the hammer price;

27% of the hammer price of amounts in excess of £40,000 up to and including £800,000;

21% of the hammer price of amounts in excess of £800,000 up to and including £4,500,000;

and 14.5% of the hammer price of any amounts in excess of £4,500,000.VAT at the current rate of 20% will be added to the Buyer's Premium and charges excluding Artists Resale Right.Buyers' ObligationsALL BIDDERS MUST AGREE THAT THEY HAVE READ AND UNDERSTOOD BONHAMS' CONDITIONS OF SALE AND AGREE TO BE BOUND BY THEM, AND AGREE TO PAY THE BUYER'S PREMIUM AND ANY OTHER CHARGES MENTIONED IN THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS. THIS AFFECTS THE BIDDERS LEGAL RIGHTS.If you have any complaints or questions about the Conditions of Sale, please contact your nearest customer services team.Payment NoticesFor payment information please refer to the sale catalog.Shipping NoticesFor information and estimates on domestic and international shipping as well as export licences please contact Bonhams Shipping Department.Related DepartmentsBooks & ManuscriptsAuction ViewingsLondon, Knightsbridge18 June 2023, 11:00 - 15:00 BST19 June 2023, 09:00 - 17:00 BST20 June 2023, 09:00 - 17:00 BST21 June 2023, 09:00 - 10:00 BSTConditions of SaleView Conditions of Sale

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Testen Sie LotSearch und seine Premium-Features 7 Tage - ohne Kosten!

Lassen Sie sich automatisch über neue Objekte in kommenden Auktionen benachrichtigen.

Suchauftrag anlegen