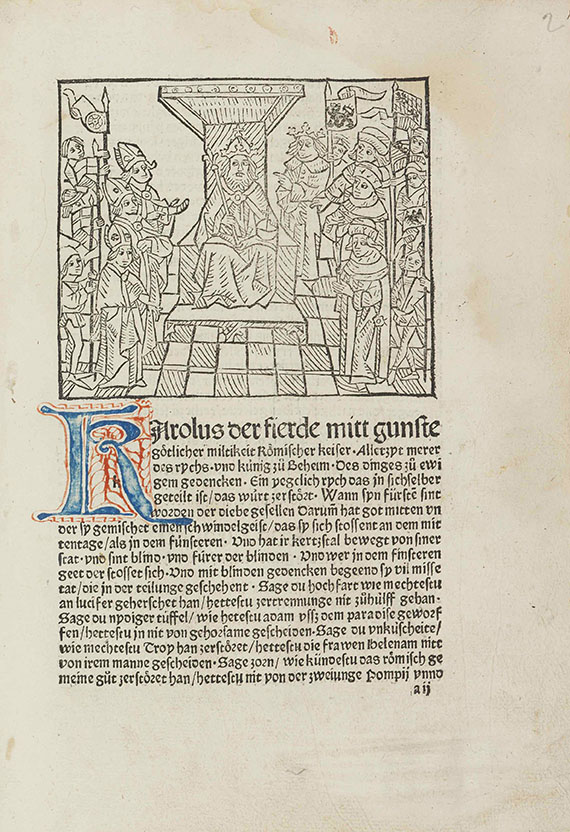

Holy Roman Empire. Nurnberg. Freie und Reichsstadt. Silver Dedication Medal from the City of Nurnberg to Emperor Charles V, 1521, :carolvs:v: - :ro:imper:, crowned and cuirassed bust right, wearing the Order of the Golden Fleece, within raised border of fourteen shields, the Emperor's personal motto plus ultra on the Pillars of Hercules, above, rev. double-headed eagle dividing date 15-21, within raised border of thirteen shields, 70mm., 209.70g (Bernhart 62; Domanig 37; Currency of Fame 77; Habich I, 18, fig.10; Mende 13; Trusted 91-92), edge hammered for presentation purposes, otherwise extremely fine, extremely rare provenance Nomos AG, TEFAF Maastricht, 14-23 March 2014, lot 46, where the provenance was given as 'From the collection of an Austrian noble family'. This is one of the most famous medals of the German Renaissance. Struck in high relief on a massive 200g silver flan, in a complex process devised by the master silversmith Hans Krafft the Elder, the medal represents German 16th century medallic art at its most spectacular. The city of Nuremberg, renowned for the spectacular work of its thriving community of goldsmiths and silversmiths, was keenly aware that the world would judge the city on the merits of this one presentation medal. The portrait of the Emperor on the obverse was from a design by Germany's most famous artist, Albrecht Dürer with input from his childhood friend, the Nuremberg Councillor Willibald Pirkheimer, while the array of heraldic shields on both sides was devised with meticulous care by the leading scholars of the day, including the humanist lawyer Johann Stabius and the clerk Lazarus Spengler. The curious political circumstances that led to the creation of the medal have been fully documented. The new Emperor, Charles V, had inherited a vast array of kingdoms and lordships through the intricies of generations of careful dynastic marriages. He was young and charismatic. Above all, he was prepared to spend large fortunes (of his own money, and of other peoples' money) in the pursuit of power. This medal was the city of Nuremberg's homage to this new star that had arisen in Europe's political firmament. And there were very practical reasons for this. The city had a long tradition of loyalty to the German Emperor, and had acquired many privileges over the years. It played a central role in the Imperial Administration, was the venue for many political assemblies, as well as a centre for the collection of Imperial taxes. Now this grand and very flattering medal was to be presented to the new young Emperor on the occasion of his first visit to the city at the very beginning of his reign, in the New Year of 1521, just after his coronation, and on the occasion of his first General Diet. It was quite simply the most important medal that any German city had yet commissioned. The drama of the events that unfolded precisely at the same time that this medal was being struck, is now the stuff of legend. Martin Luther had recently shaken the established Church by his preaching, and, in an increasingly hostile environment, attacks and counter-attacks were growing in frequency and ferocity. At the last minute it was decided that Luther should present his arguments in person before the Emperor, and so he was commanded to appear at the first Diet and present his defence. But now there was a clear and most embarrassing conflict of interests. The City of Nuremberg was not neutral in this debate. Many of her most prominent scholars and lawyers, including the men involved in creating this spectacular medal for the emperor, were known to be sympathetic to Martin Luther. Indeed, Willibald Pirkheimer and Lazarus Spengler were named as 'accomplices' in the Bull of Excommunication published against Luther at the beginning of January, just weeks before the Diet was due to take place, and they were also excommunicated. The Bull went on the declare that anyone found to be helping or even agreeing with Luther, was likewise

Holy Roman Empire. Nurnberg. Freie und Reichsstadt. Silver Dedication Medal from the City of Nurnberg to Emperor Charles V, 1521, :carolvs:v: - :ro:imper:, crowned and cuirassed bust right, wearing the Order of the Golden Fleece, within raised border of fourteen shields, the Emperor's personal motto plus ultra on the Pillars of Hercules, above, rev. double-headed eagle dividing date 15-21, within raised border of thirteen shields, 70mm., 209.70g (Bernhart 62; Domanig 37; Currency of Fame 77; Habich I, 18, fig.10; Mende 13; Trusted 91-92), edge hammered for presentation purposes, otherwise extremely fine, extremely rare provenance Nomos AG, TEFAF Maastricht, 14-23 March 2014, lot 46, where the provenance was given as 'From the collection of an Austrian noble family'. This is one of the most famous medals of the German Renaissance. Struck in high relief on a massive 200g silver flan, in a complex process devised by the master silversmith Hans Krafft the Elder, the medal represents German 16th century medallic art at its most spectacular. The city of Nuremberg, renowned for the spectacular work of its thriving community of goldsmiths and silversmiths, was keenly aware that the world would judge the city on the merits of this one presentation medal. The portrait of the Emperor on the obverse was from a design by Germany's most famous artist, Albrecht Dürer with input from his childhood friend, the Nuremberg Councillor Willibald Pirkheimer, while the array of heraldic shields on both sides was devised with meticulous care by the leading scholars of the day, including the humanist lawyer Johann Stabius and the clerk Lazarus Spengler. The curious political circumstances that led to the creation of the medal have been fully documented. The new Emperor, Charles V, had inherited a vast array of kingdoms and lordships through the intricies of generations of careful dynastic marriages. He was young and charismatic. Above all, he was prepared to spend large fortunes (of his own money, and of other peoples' money) in the pursuit of power. This medal was the city of Nuremberg's homage to this new star that had arisen in Europe's political firmament. And there were very practical reasons for this. The city had a long tradition of loyalty to the German Emperor, and had acquired many privileges over the years. It played a central role in the Imperial Administration, was the venue for many political assemblies, as well as a centre for the collection of Imperial taxes. Now this grand and very flattering medal was to be presented to the new young Emperor on the occasion of his first visit to the city at the very beginning of his reign, in the New Year of 1521, just after his coronation, and on the occasion of his first General Diet. It was quite simply the most important medal that any German city had yet commissioned. The drama of the events that unfolded precisely at the same time that this medal was being struck, is now the stuff of legend. Martin Luther had recently shaken the established Church by his preaching, and, in an increasingly hostile environment, attacks and counter-attacks were growing in frequency and ferocity. At the last minute it was decided that Luther should present his arguments in person before the Emperor, and so he was commanded to appear at the first Diet and present his defence. But now there was a clear and most embarrassing conflict of interests. The City of Nuremberg was not neutral in this debate. Many of her most prominent scholars and lawyers, including the men involved in creating this spectacular medal for the emperor, were known to be sympathetic to Martin Luther. Indeed, Willibald Pirkheimer and Lazarus Spengler were named as 'accomplices' in the Bull of Excommunication published against Luther at the beginning of January, just weeks before the Diet was due to take place, and they were also excommunicated. The Bull went on the declare that anyone found to be helping or even agreeing with Luther, was likewise

Testen Sie LotSearch und seine Premium-Features 7 Tage - ohne Kosten!

Lassen Sie sich automatisch über neue Objekte in kommenden Auktionen benachrichtigen.

Suchauftrag anlegen