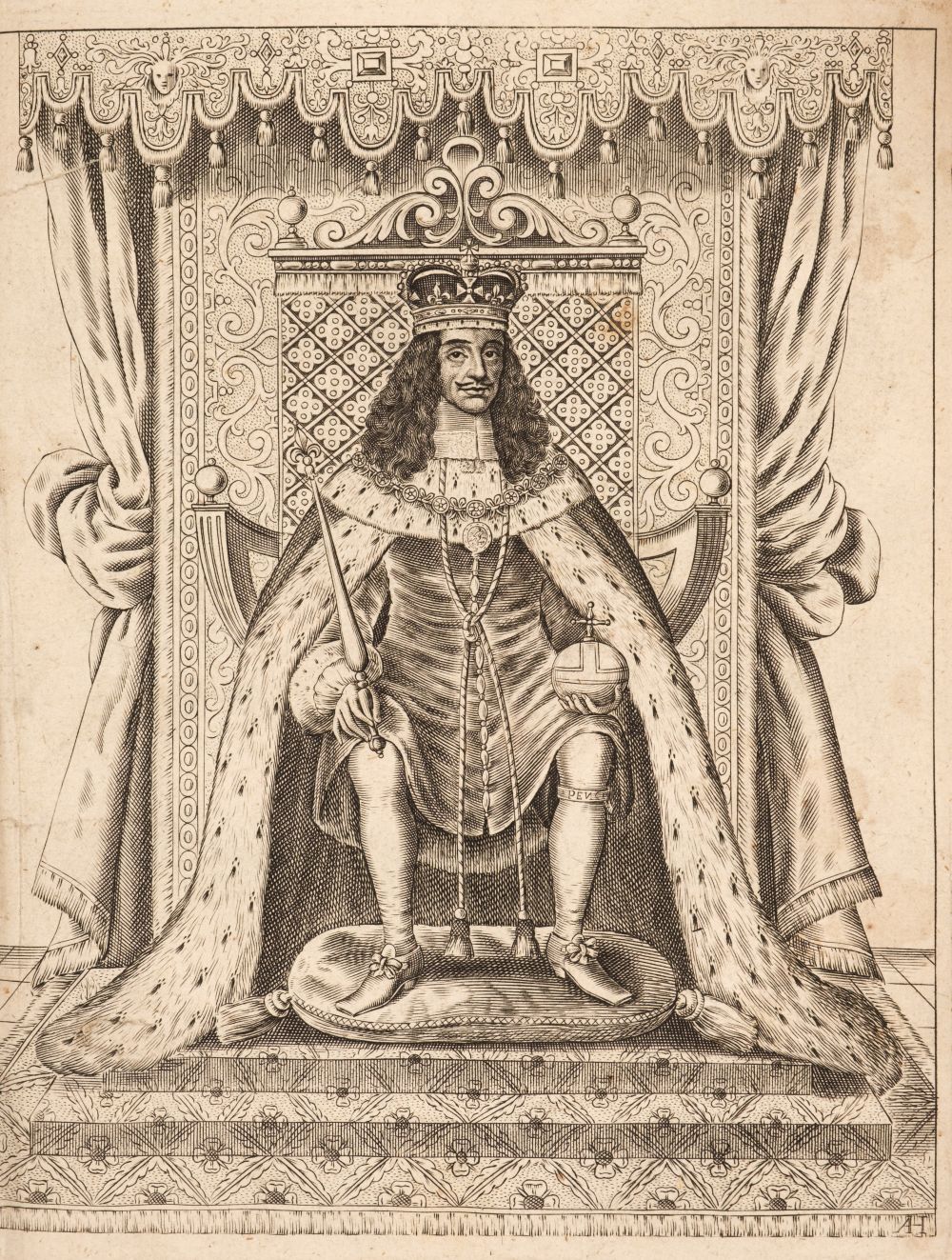

King Charles II

"The Declaration of Breda", signed at the head ("Charles R"), THE DOCUMENT THAT ENABLED THE RESTORATION OF THE MONARCHY

Proclamation addressed "To all our loving Subjects of what degree or quality soever", making an appeal in the face of the "generall Distraction and Confusion which is spread over the Whole Kingdome", outlining the terms on which he would return to Britain and assume the throne, "at Our Court at Breda this 4/14 day of Aprill 1660, in the twelfth yeare of Our Reigne", 4 pages, folio (333 x 230mm, watermark of a crowned Medici coat of arms), with papered privy seal, later numbering in ink and pencil ("No 191", "201", and "5", the last cancelled), later neat repairs to nicks and short fold tears affecting one letter of one word, remains of guard, dust staining, creases

“…To all Our loving Subjects of what degree or quality soever, Greeting. If the general Distraction and Confusion which is spread over the whole Kingdome, doth not awaken all men to a desire and longing that those Wounds which have so many yeares together been kept bleeding may be bound up, all We can say will be to noe purpose; However after this long Silence, We have thought it Our Duty to Declare how much We desire to contribute thereunto; and that as We can never give over the hope in good time to obteyne the possession of that Right, which God and Nature hath made Our Due; soe We doe make it Our dayly Suite to the Devine Providence, That he will in Compassion to Us and Our Subjects, after so long misery & sufferings, remitt and put Us into a quiet & peaceable possession of that Our Right with as little bloud and dammage to our People, as is possible: Nor doe We desire more to enjoy what is Ours, then that all Our Subjects may enjoy what by Law is theirs, by a full & entire Administration of Justice throughout the Land, & by extending Our Mercy where it is wanted & deserved…”

A KEY DOCUMENT IN BRITAIN'S ROYAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY, AND THE COPY READ OUT BY SAMUEL PEPYS TO THE NAVY TO WIN THEM OVER TO THE KING, as he was to record in his diary: “the commanders all came on board, and the council set in the coach… where I read the letter and declaration”. The Declaration of Breda struck a note of reconciliation that brought peace to a nation in turmoil, ensured that the monarchy was restored without further civil war, and was an important step in the development of Britain’s constitutional monarchy. It marked an end to twenty years of revolution, although it certainly did not turn the clock back to 1640. King Charles signed five copies of the Declaration. Only two of these copies survive and the current example, which is the only copy in private hands, was the copy that Samuel Pepys read from at the meeting at which the navy made its decision to support the King.

The execution of King Charles I in January 1649 had unmoored Britain from her traditional constitution. England, Scotland, and Ireland had been governed by a series of short-lived modes of government, including a Commonwealth and a Protectorate, in the years that followed. Stability of a kind was provided by the personal power of Oliver Cromwell, but his death in September 1658 soon exposed the shallow roots of the Protectorate. 1659 saw an increasingly chaotic series of changes in government, making clear to increasing numbers of people that the route to stability was the return of the king. The monarchy that was re-established in 1660 has now held in England and Scotland uninterrupted for more than 350 years.

The revolutionary years had revealed to all sides the extent to which power came through control of the standing army. In early 1660 that power was in the hands of General George Monck. He had been commander of the army in Scotland until, in the name of Parliament, he had rebelled against the military junta that had assumed control in London the previous summer. He faced down the demoralised and divided English armies and marched on London in January 1660. Once he was safely in control in London, Monck used his authority to recall Parliament. On 8 March the Commons passed a bill for new elections and 16 March the Long Parliament, which had originally been called in 1640, was finally dissolved. The next day Monck met secretly with Sir John Granville, the King's clandestine representative. He pledged allegiance to Charles II and gave advice as to what terms Charles should offer in order to win support for his return.

Sir John Granville rode immediately with another royalist conspirator, Viscount Mordaunt, to the court in exile. Charles was being offered an opportunity that he could hardly have imagined even just a few months earlier. He had spent more than ten years in exile, plotting a series of failed conspiracies and insurrections: as recently as August 1659 Mordaunt had been the chief plotter in Booth's Uprising, a royalist rebellion in Cheshire that had been penetrated by Commonwealth agents and rapidly suppressed by a Parliamentary army under Major General Lambert. Just a few months later, petitions were being published openly calling for the restoration of the monarchy, royalist sympathisers appeared to be in the ascendant in the elections, and the military commander who controlled the country was offering his support. This was Charles’s moment, but the situation in Britain was incredibly fluid and one wrong move could lose him his kingdom forever.

The King’s first step, recommended by Monck, was to move from Brussels (Spanish Catholic territory) to Breda, just across the border in the Protestant Netherlands. It was from there that he issued a proclamation announcing the terms on which he would take the throne. The Declaration of Breda was drafted by the King and his closest councillors: Sir Edward Hyde, Sir Edward Nicholas, and the Earl of Ormond. It strikes a powerful tone of reconciliation with its hope that the restoration of the king would bind the wounds of civil war, its expression of compassion for all his subjects, and its promise of mercy. The Declaration also makes specific commitments which were heavily influenced by the advice Monck had given Grenville. The first was to “grant a free & generall Pardon […] to all Our Subjects of what degree or quality soever, who […] returne to the Loyalty & Obedience of good Subjects; Excepting only such Persons as shall hereafter be excepted by Parliament”. This is the origin of the Act of Oblivion which ensured that former republicans, excepting only the regicides, would not be persecuted by the resurgent royalists. Charles explicitly promises to leave aside wish for revenge for past wrongs: “We desiring & ordaining that hence forward all Notes of discord, Separation & difference of Partys, be utterly abolished among all Our Subjects, whom We invite and conjure to a perfect Union among themselves, under Our Protection, for the Resettlement of Our just Rights & theirs in a free Parliament, by which upon the Word of a King We will be advised”. Secondly, and further to this end, “Wee doe Declare a Liberty to tender Consciences, & that no man shall be disquieted or call'd in question for differences in Opinion in matter of Religion, which doe not disturbe the Peace of the Kingdome”. Finally, he promises to respect the property rights of those – most notably soldiers – who had purchased land during the Interregnum, and to settle any arrears of pay in the army.

Grenville and Mordaunt were once again entrusted as the King’s emissaries and set out with five signed copies of the Declaration, including the present example. Each copy was enclosed with a covering letter for its intended recipient: (i) General Monck, for the Council of State; (ii) the Speaker of the Commons; (iii) the House of Lords; (iv) Generals Monck and Montagu, Generals at Sea (i.e. commanders of the navy); (v) and the Lord Mayor of London. The King’s messengers arrived to find that Sir John Lambert was calling on supporters of the Good Old Cause to rally to his standard, which he raised at the battlefield of Edgehill. Lambert's republican insurrection soon sputtered out, and Grenville and Mordaunt were treated to the sight of one of Cromwell’s greatest generals, and the man who had suppressed a royalist uprising eight months earlier, being brought as a prisoner to the Tower of London. It was against this tumultuous backdrop that the message from the King was secretly delivered to Monck. A few days later, on 25 April, the Convention Parliament assembled. Monck spent the first days gauging the mood of the new Parliament before, on 1 May, he played his trump card:

“he came into the house, and told them ‘one sir John Greenvil, who was a servant of the king’s, had brought him a letter from his majesty; which he had in his hand, but would not presume to open it without their direction; and that the same gentleman was at the door, and had a letter to the house’, which was no sooner said, than with a general acclamation he was called for […] the house immediately called to have both letters read, that to the general, and that to the speaker: which being done, the declaration was as greedily called for, and read.” (Clarendon, History of the Rebellion, vol. 7, p.478)

The effect was immediate, and electric. The House rose in thanks, voted the king an immediate subsidy of £50,000, established a committee to write a reply, and ordered that the declaration be printed. The other copies Charles had prepared were rapidly sent out, and this is when the current copy came to have its moment in Britain’s national story. Support from Parliament was not enough to secure the throne. Another key power base was the fleet, which Charles in his covering letter called “the walls of the kingdom”. The navy was commanded jointly by Monck and Edward Montagu. It was the latter who was with the fleet off the Kentish coast. Montagu was secretly committed to the King and had already been working to purge the navy of republicans; he worked closely with his secretary, none other than Samuel Pepys, to minimise the chances of dissent when the Declaration was read to the fleet. The current lot is the copy of the document that was sent by Monck to Montagu and was handled and read by Pepys at a critical meeting of the fleet on Montagu’s flagship, the Naseby. Pepys describes this meeting in his diary entry for 3 May 1660 this meeting, along with Montagu’s careful preparations to ensure that the meeting go the king’s way:

"This morning my Lord showed me the King's declaration and his letter to the two Generalls to be communicated to the fleet. The contents of the letter are his offer of grace to all that will come in within 40 days, only excepting them that the Parliament shall hereafter except. That the sale of lands during these troubles and all other things, shall be left to the Parliament, by which he will stand. The letter dated at Breda, April 4/14 1660, in the 12th year of his Raigne. Upon the receipt of it this morning by an express, Mr. [Henry] Phillips, one of the messengers of the Council from Generall Monke, my Lord summoned a council of war, and in the meantime did dictate to me how he would have the vote ordered which he would have pass this council. Which done, the commanders all came on board, and the council set in the coach (the first council of war that hath been in my time), where I read the letter and declaration; and while they were discoursing upon it, I seemed to draw up a vote; which being offered, they passed. Not one man seemed to say no to it, though I am confident many in their hearts were against it. After this was done, I went up to the Quarter-deck with my Lord and the commanders, and there read both the papers and the vote; which done, and demanding their opinion, the seamen did all of them cry out 'God bless King Charles' with the greatest joy imaginable" (The Diary of Samuel Pepys, eds Latham and Matthews).

It was through this document, then, and in the hands of Pepys, that the “walls of the kingdom” were won for the king.

Events continued to move quickly in the days that followed. Parliament proclaimed King Charles (dating his accession to 1649) on 8 May, and on the same day the Declaration of Breda appeared in print. Pepys records that when he was busily copying documents he ensured that “to all the copies of the vote of the council of war I put my name, that if it should come in print my name maybe at it” (4 May) – less than a week later he was delighted to find his name at the foot of the printed version of the historic document. Meanwhile Montagu quickly ordered the removal the Naseby’s figurehead, Oliver Cromwell crowned with laurels, then set sail for Scheveningen in the Netherlands to bring back the king. Pepys accompanied Montagu and his diary provides a typically vivid account of the extraordinary few days in the Netherlands as the ever-growing royal court prepared to return home. The royal party set sail on 23 May, but not before renaming the ship HMS Royal Charles. Pepys records how the king regaled the quarterdeck with the story of his dramatic escape after the Battle of Worcester. Less than a week later, on 29 May, his thirtieth birthday, King Charles II entered London uncontested. One of the most dramatic changes in British constitutional history had been accomplished in a matter of weeks and without significant bloodshed.

Of the five copies of the Declaration that were sent from Breda on 14 April 1660, only two are known to survive. One is in the Parliamentary Archives (PIC/P/283); this is the other. Seal and signature are the same in both copies, but they are written on different paper stocks and in different scribal hands. The current copy remained in the family archive of Edward Montagu (later Earl of Sandwich) until it was sold at auction in 1985. It is the only copy of the Declaration of Breda in private hands, and Pepys’s diary shows that it was a vital prop in a scene of great historical importance.

King Charles II

"The Declaration of Breda", signed at the head ("Charles R"), THE DOCUMENT THAT ENABLED THE RESTORATION OF THE MONARCHY

Proclamation addressed "To all our loving Subjects of what degree or quality soever", making an appeal in the face of the "generall Distraction and Confusion which is spread over the Whole Kingdome", outlining the terms on which he would return to Britain and assume the throne, "at Our Court at Breda this 4/14 day of Aprill 1660, in the twelfth yeare of Our Reigne", 4 pages, folio (333 x 230mm, watermark of a crowned Medici coat of arms), with papered privy seal, later numbering in ink and pencil ("No 191", "201", and "5", the last cancelled), later neat repairs to nicks and short fold tears affecting one letter of one word, remains of guard, dust staining, creases

“…To all Our loving Subjects of what degree or quality soever, Greeting. If the general Distraction and Confusion which is spread over the whole Kingdome, doth not awaken all men to a desire and longing that those Wounds which have so many yeares together been kept bleeding may be bound up, all We can say will be to noe purpose; However after this long Silence, We have thought it Our Duty to Declare how much We desire to contribute thereunto; and that as We can never give over the hope in good time to obteyne the possession of that Right, which God and Nature hath made Our Due; soe We doe make it Our dayly Suite to the Devine Providence, That he will in Compassion to Us and Our Subjects, after so long misery & sufferings, remitt and put Us into a quiet & peaceable possession of that Our Right with as little bloud and dammage to our People, as is possible: Nor doe We desire more to enjoy what is Ours, then that all Our Subjects may enjoy what by Law is theirs, by a full & entire Administration of Justice throughout the Land, & by extending Our Mercy where it is wanted & deserved…”

A KEY DOCUMENT IN BRITAIN'S ROYAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY, AND THE COPY READ OUT BY SAMUEL PEPYS TO THE NAVY TO WIN THEM OVER TO THE KING, as he was to record in his diary: “the commanders all came on board, and the council set in the coach… where I read the letter and declaration”. The Declaration of Breda struck a note of reconciliation that brought peace to a nation in turmoil, ensured that the monarchy was restored without further civil war, and was an important step in the development of Britain’s constitutional monarchy. It marked an end to twenty years of revolution, although it certainly did not turn the clock back to 1640. King Charles signed five copies of the Declaration. Only two of these copies survive and the current example, which is the only copy in private hands, was the copy that Samuel Pepys read from at the meeting at which the navy made its decision to support the King.

The execution of King Charles I in January 1649 had unmoored Britain from her traditional constitution. England, Scotland, and Ireland had been governed by a series of short-lived modes of government, including a Commonwealth and a Protectorate, in the years that followed. Stability of a kind was provided by the personal power of Oliver Cromwell, but his death in September 1658 soon exposed the shallow roots of the Protectorate. 1659 saw an increasingly chaotic series of changes in government, making clear to increasing numbers of people that the route to stability was the return of the king. The monarchy that was re-established in 1660 has now held in England and Scotland uninterrupted for more than 350 years.

The revolutionary years had revealed to all sides the extent to which power came through control of the standing army. In early 1660 that power was in the hands of General George Monck. He had been commander of the army in Scotland until, in the name of Parliament, he had rebelled against the military junta that had assumed control in London the previous summer. He faced down the demoralised and divided English armies and marched on London in January 1660. Once he was safely in control in London, Monck used his authority to recall Parliament. On 8 March the Commons passed a bill for new elections and 16 March the Long Parliament, which had originally been called in 1640, was finally dissolved. The next day Monck met secretly with Sir John Granville, the King's clandestine representative. He pledged allegiance to Charles II and gave advice as to what terms Charles should offer in order to win support for his return.

Sir John Granville rode immediately with another royalist conspirator, Viscount Mordaunt, to the court in exile. Charles was being offered an opportunity that he could hardly have imagined even just a few months earlier. He had spent more than ten years in exile, plotting a series of failed conspiracies and insurrections: as recently as August 1659 Mordaunt had been the chief plotter in Booth's Uprising, a royalist rebellion in Cheshire that had been penetrated by Commonwealth agents and rapidly suppressed by a Parliamentary army under Major General Lambert. Just a few months later, petitions were being published openly calling for the restoration of the monarchy, royalist sympathisers appeared to be in the ascendant in the elections, and the military commander who controlled the country was offering his support. This was Charles’s moment, but the situation in Britain was incredibly fluid and one wrong move could lose him his kingdom forever.

The King’s first step, recommended by Monck, was to move from Brussels (Spanish Catholic territory) to Breda, just across the border in the Protestant Netherlands. It was from there that he issued a proclamation announcing the terms on which he would take the throne. The Declaration of Breda was drafted by the King and his closest councillors: Sir Edward Hyde, Sir Edward Nicholas, and the Earl of Ormond. It strikes a powerful tone of reconciliation with its hope that the restoration of the king would bind the wounds of civil war, its expression of compassion for all his subjects, and its promise of mercy. The Declaration also makes specific commitments which were heavily influenced by the advice Monck had given Grenville. The first was to “grant a free & generall Pardon […] to all Our Subjects of what degree or quality soever, who […] returne to the Loyalty & Obedience of good Subjects; Excepting only such Persons as shall hereafter be excepted by Parliament”. This is the origin of the Act of Oblivion which ensured that former republicans, excepting only the regicides, would not be persecuted by the resurgent royalists. Charles explicitly promises to leave aside wish for revenge for past wrongs: “We desiring & ordaining that hence forward all Notes of discord, Separation & difference of Partys, be utterly abolished among all Our Subjects, whom We invite and conjure to a perfect Union among themselves, under Our Protection, for the Resettlement of Our just Rights & theirs in a free Parliament, by which upon the Word of a King We will be advised”. Secondly, and further to this end, “Wee doe Declare a Liberty to tender Consciences, & that no man shall be disquieted or call'd in question for differences in Opinion in matter of Religion, which doe not disturbe the Peace of the Kingdome”. Finally, he promises to respect the property rights of those – most notably soldiers – who had purchased land during the Interregnum, and to settle any arrears of pay in the army.

Grenville and Mordaunt were once again entrusted as the King’s emissaries and set out with five signed copies of the Declaration, including the present example. Each copy was enclosed with a covering letter for its intended recipient: (i) General Monck, for the Council of State; (ii) the Speaker of the Commons; (iii) the House of Lords; (iv) Generals Monck and Montagu, Generals at Sea (i.e. commanders of the navy); (v) and the Lord Mayor of London. The King’s messengers arrived to find that Sir John Lambert was calling on supporters of the Good Old Cause to rally to his standard, which he raised at the battlefield of Edgehill. Lambert's republican insurrection soon sputtered out, and Grenville and Mordaunt were treated to the sight of one of Cromwell’s greatest generals, and the man who had suppressed a royalist uprising eight months earlier, being brought as a prisoner to the Tower of London. It was against this tumultuous backdrop that the message from the King was secretly delivered to Monck. A few days later, on 25 April, the Convention Parliament assembled. Monck spent the first days gauging the mood of the new Parliament before, on 1 May, he played his trump card:

“he came into the house, and told them ‘one sir John Greenvil, who was a servant of the king’s, had brought him a letter from his majesty; which he had in his hand, but would not presume to open it without their direction; and that the same gentleman was at the door, and had a letter to the house’, which was no sooner said, than with a general acclamation he was called for […] the house immediately called to have both letters read, that to the general, and that to the speaker: which being done, the declaration was as greedily called for, and read.” (Clarendon, History of the Rebellion, vol. 7, p.478)

The effect was immediate, and electric. The House rose in thanks, voted the king an immediate subsidy of £50,000, established a committee to write a reply, and ordered that the declaration be printed. The other copies Charles had prepared were rapidly sent out, and this is when the current copy came to have its moment in Britain’s national story. Support from Parliament was not enough to secure the throne. Another key power base was the fleet, which Charles in his covering letter called “the walls of the kingdom”. The navy was commanded jointly by Monck and Edward Montagu. It was the latter who was with the fleet off the Kentish coast. Montagu was secretly committed to the King and had already been working to purge the navy of republicans; he worked closely with his secretary, none other than Samuel Pepys, to minimise the chances of dissent when the Declaration was read to the fleet. The current lot is the copy of the document that was sent by Monck to Montagu and was handled and read by Pepys at a critical meeting of the fleet on Montagu’s flagship, the Naseby. Pepys describes this meeting in his diary entry for 3 May 1660 this meeting, along with Montagu’s careful preparations to ensure that the meeting go the king’s way:

"This morning my Lord showed me the King's declaration and his letter to the two Generalls to be communicated to the fleet. The contents of the letter are his offer of grace to all that will come in within 40 days, only excepting them that the Parliament shall hereafter except. That the sale of lands during these troubles and all other things, shall be left to the Parliament, by which he will stand. The letter dated at Breda, April 4/14 1660, in the 12th year of his Raigne. Upon the receipt of it this morning by an express, Mr. [Henry] Phillips, one of the messengers of the Council from Generall Monke, my Lord summoned a council of war, and in the meantime did dictate to me how he would have the vote ordered which he would have pass this council. Which done, the commanders all came on board, and the council set in the coach (the first council of war that hath been in my time), where I read the letter and declaration; and while they were discoursing upon it, I seemed to draw up a vote; which being offered, they passed. Not one man seemed to say no to it, though I am confident many in their hearts were against it. After this was done, I went up to the Quarter-deck with my Lord and the commanders, and there read both the papers and the vote; which done, and demanding their opinion, the seamen did all of them cry out 'God bless King Charles' with the greatest joy imaginable" (The Diary of Samuel Pepys, eds Latham and Matthews).

It was through this document, then, and in the hands of Pepys, that the “walls of the kingdom” were won for the king.

Events continued to move quickly in the days that followed. Parliament proclaimed King Charles (dating his accession to 1649) on 8 May, and on the same day the Declaration of Breda appeared in print. Pepys records that when he was busily copying documents he ensured that “to all the copies of the vote of the council of war I put my name, that if it should come in print my name maybe at it” (4 May) – less than a week later he was delighted to find his name at the foot of the printed version of the historic document. Meanwhile Montagu quickly ordered the removal the Naseby’s figurehead, Oliver Cromwell crowned with laurels, then set sail for Scheveningen in the Netherlands to bring back the king. Pepys accompanied Montagu and his diary provides a typically vivid account of the extraordinary few days in the Netherlands as the ever-growing royal court prepared to return home. The royal party set sail on 23 May, but not before renaming the ship HMS Royal Charles. Pepys records how the king regaled the quarterdeck with the story of his dramatic escape after the Battle of Worcester. Less than a week later, on 29 May, his thirtieth birthday, King Charles II entered London uncontested. One of the most dramatic changes in British constitutional history had been accomplished in a matter of weeks and without significant bloodshed.

Of the five copies of the Declaration that were sent from Breda on 14 April 1660, only two are known to survive. One is in the Parliamentary Archives (PIC/P/283); this is the other. Seal and signature are the same in both copies, but they are written on different paper stocks and in different scribal hands. The current copy remained in the family archive of Edward Montagu (later Earl of Sandwich) until it was sold at auction in 1985. It is the only copy of the Declaration of Breda in private hands, and Pepys’s diary shows that it was a vital prop in a scene of great historical importance.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Testen Sie LotSearch und seine Premium-Features 7 Tage - ohne Kosten!

Lassen Sie sich automatisch über neue Objekte in kommenden Auktionen benachrichtigen.

Suchauftrag anlegen