Leonardo da Vinci Trattato della pittura. Manuscript on paper. [Rome: workshop of Cassiano dal Pozzo, ca 1633-1639]

Unique among the prepublication copies of Leonardo's Trattato della pittura, this manuscript in the Brooker collection is the only copy that contains the small sketches known as Urbinate drawings and copies of Poussin's illustrations. The Brooker manuscript is classified as C,2 in Kate Trauman Steinitz's essential catalogue, Leonardo da Vinci's Trattato della pittura (Copenhagen 1958, pages 80-82). It appears as C1 in the classification of nearly fifty pre-publication manuscripts on the website dedicated to the Treatise on Painting. The University of Virginia (Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities) maintains the website, which is accessible via www.treatiseonpainting.org.

Steinitz traced the manuscript's history back to the early 18th century. Before its current owner, the Brooker manuscript belonged to the Marquis Hubert de Ganay, who inherited it from his aunt, the Comtesse de Béhague (Béarn). Before that, the manuscript passed through the hands of several individuals, including Huquier, Antoine-Auguste Renouard, Count Thibaudeau, and Ambroise Firmin-Didot- Recent research casts doubt on Steinitz's supposition (based on notes by Renouard) that Roland Fréart de Chambray used the Brooker manuscript, and that Nicolas Poussin formerly owned it.

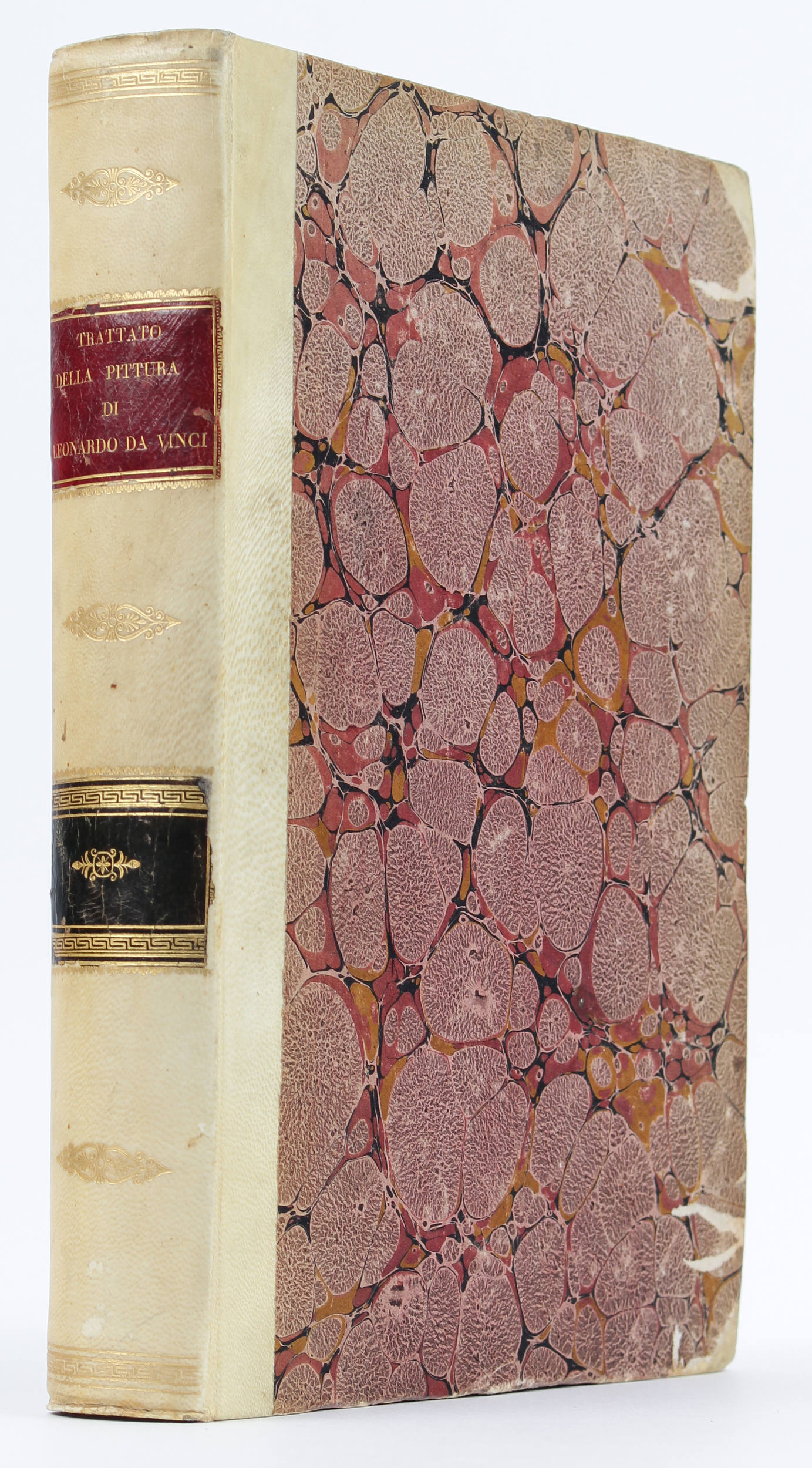

The manuscript is bound in a striking red morocco leather binding embossed with the arms of Monsieur de Champlâtreux, son of Chancellor Matthieu Molé, President of the French parliament. Steinitz used this detail to date the binding to before 1656, the year Molé died. However, further research has revealed that the binding was reused from another volume entitled Nouvelles observations et coniectures sur l'iris by Marin Cureau de la Chambre (Paris: Jacques Langlois 1651). T. Kimball Brooker has suggested that the binding dates from the 18th century, as indicated by the disparity between the size of the book block and the binding, traces of the former title "SUR/L'IRIS" on the spine, the marbled endpapers, and the window mounting of text and image on grey paper.

The date of the manuscript is significantly earlier. It divides into five parts: [1] Trattato text and sketches; [2] added chapters; [3] Mazenta's memoir; [4] checklist of chapter titles; [5] copies of illustrations to be used in the publication of the Trattato. The original documents, from which the copies in the Brooker manuscript derive, belonged to Cassiano dal Pozzo (1588-1657), a well-known collector and bibliophile, supporter of scientific research, early patron of Nicolas Poussin and a prominent influencer of culture in Rome during the pontificate of Pope Urban VIII. Internal evidence and comparison with other known copies from Dal Pozzo's atelier suggest that the manuscript offered for sale was started before 1633 and finished by 1639.

Dal Pozzo directed the project to publish Leonardo's writings under the auspices of Cardinal Francesco Barberini (1597-1679), nephew to Urban VIII. Dal Pozzo supported early modern science as a member of the select Accademia dei Lincei, a scientific society founded by Federico Cesi (1585-1630). Dal Pozzo helped edit Galileo's controversial text, The Assayer, and arranged funding for publications on the flora and fauna of the new world, for a volume on citrus fruits, and for many other texts on the natural world. He compiled a mega-collection of illustrated sheets of antiquities, inscriptions, flora, fauna, fossils, fungi, and other curiosities of nature known as the Museo Cartaceo (Paper Museum).

Dal Pozzo owned a copy of Leonardo's writings when he arrived in Rome from Florence in 1612 (unpublished research of Pauline Maguire). Around 1634, Dal Pozzo gave this copy (modern designation vb), now in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, to Cardinal Barberini for the Barberini Library. It bears the collocation Barb. Lat. 4304. Early in the publication project, Dal Pozzo compiled m3 (Biblioteca Ambrosiana MS H228 inf.), a text derived from a different source than vb's. He commissioned original drawings from Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665) and original diagrams from the scientific researcher and mathematician, Gaspare Berti (1601-1643), to be used for engravings in a lavish publication. Both vb and m3 were used to compile the manuscript offered for sale.

Part 1: Brooker (fols.1r-101r) is a copy of the text and sketches of Dal Pozzo's manuscript vb (BAV MS Barb. Lat. 4304). The corrections and supplemental text inserted in the margins and between lines of text derive from m3. Sparti (2003) incorrectly surmised that the annotations were by Trichet du Fresne, an attribution that cannot be sustained by handwriting comparisons nor by what we can firmly ascertain about the early date of this text. The copy from vb was probably executed before Dal Pozzo employed Poussin and Berti to illustrate the text of m3, which took place in 1633-1634. Dal Pozzo updated the manuscript with additions and corrections years before Trichet du Fresne became involved in the Trattato publication project. Thus, this copy was an important point of reference during the years in which Leonardo's Trattato took final form in Rome.

Cassiano dal Pozzo's publication project included an effort to expand the number of chapters. The Milanese cleric Ambrogio Mazenta was promoted to Vicar and transferred to Rome in 1635, at which time he informed Dal Pozzo of the presence of autograph Leonardo manuscripts in Milan in the collection of Galeazzo Arconati (1580-1649). He prepared a memoir of the history of the manuscripts, which the Mazenta family had owned between 1589 and 1608.

Part 3: Brooker (fols. 126r-132r) is a copy of Mazenta's memoir, the original of which is bound in m2 (Biblioteca Ambrosiana MS H 227 inf.).

Dal Pozzo engaged the cooperation of Arconati to extract passages relevant to painting from the autograph manuscripts as a favor to Cardinal Barberini in return for favors for his son, Luigi Maria, and other compatriots. By 1636, Arconati had donated the notebooks to the Ambrosiana, but maintained access to them. Arconati eventually sent to Rome four separate compilations of excerpts and a large volume on hydraulics, conserved in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

Part 2: Brooker (fols. 102-115v) is a copy of the first compilation of excerpts (the so-called "added chapters") that Dal Pozzo received, the original of which is bound in m2. The corresponding images (fols. 116-125) are missing from the source manuscript (m2) but are found in two other copies, m4 (BAMi MS H229 inf.) and n1, the elegant copy in Naples known as the Codex Corazza.

The "added chapters" pertain to light and shade, plants, movement, and perspective. Their inclusion in this manuscript copy and in another that went to France indicate that Dal Pozzo hoped the French publication would support his intention to include all of Leonardo's known writings on painting. The French editors chose not to include this material. The Traitté de la peinture (lots 550-551) included only the chapters in m3. The co-published Italian edition (lot 552), edited by Raphael Trichet du Fresne, was expanded to include reprints of Leon Battista Alberti's Della pittura and Della scultura and Lives of Leonardo da Vinci and Leon Battista Alberti written by Du Fresne.

To ensure the accuracy of his m3 text, Dal Pozzo sent Arconati a list of chapters that he found "difficult to understand" and asked Arconati to check them against Leonardo's original writings and another copy of the Trattato in Milan, presumably the Codex Pinellianus, m1 (Biblioteca Ambrosiana D 467 inf.).

Part 4: Brooker (fols. 132r-133r) is a copy of the "checklist" of chapter headings from Dal Pozzo's m3.

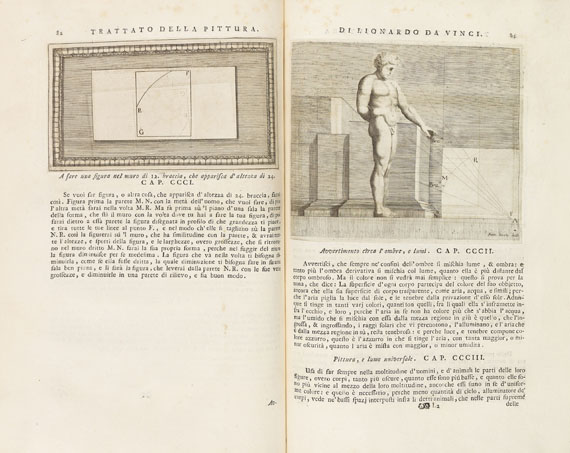

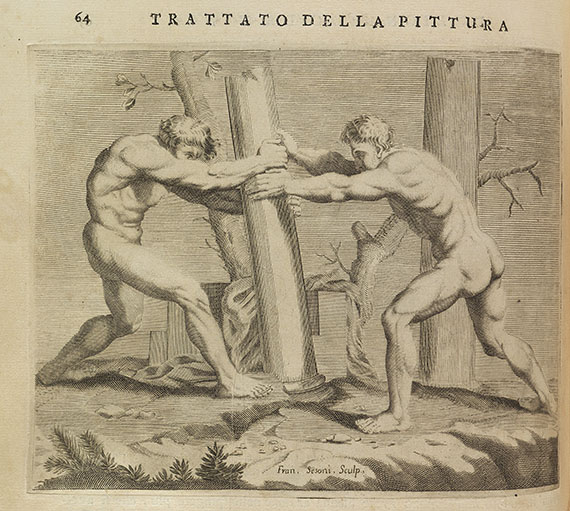

Part 5: Brooker (fols. 134-162) contains pen and wash copies of fifty-three diagrams and figures prepared for m3. The size of the figure drawings conforms to Nicolas Poussin's originals and were most likely made by tracing or lucidare, as were other copies in the Poussin atelier. Barone (2009) found that Poussin designed all the figures to the same scale for ease of replication. While 20th-century connoisseurs determined that the drawings in m3 were Poussin's originals, 17th-century writers considered the copies made in his studio to be authentic. This is certainly one reason that the pages were mounted and bound together as a collector's item.

Plans to publish Leonardo's writings on painting moved to Paris between late 1640, when Poussin travelled there to work for Louis XIII, and 1644, when Urban VIII died. Paris was a prominent center for book publication. The Trattato played a special role in the plans of Cardinal Richelieu (1585-1642) and François Sublet de Noyers (1589-1645) to bring Italian culture to France. They employed French artists in Rome to make copies of famous paintings and plaster casts of antique statues to be used for the education of artists at their own academy of art. The publication was delayed until 1651 due to the deaths of Richelieu and King Louis XIII, the fall from grace of Sublet, and years of political turmoil during the regency period of Louis XIV, but a French académie de peinture et de sculpture was founded in 1648.

The publications in 1651 were initially a great success. Charles Errard (1606-1689), first painter to the king, supervised the volumes, preparing designs for the engravers to be used in the printed editions. He standardized the column width by adding fictive mats and frames around the diagrams and landscapes and adding landscape or architectural backgrounds to the figure drawings. He oversaw the challenging task of printing each page twice: once for the text on a relief press, again for the illustrations on an intaglio press — a difficult task requiring precise alignment at a time when printing technology lacked precision devices. Each printed copy varies slightly from others as a result. The quantity of paper reserved for the publication bearing the watermark of Richelieu turned out to be inadequate, with the result that some copies include sheets or quires with different paper.

The Traitté was adopted as an instructional text by the royal Académie de peinture et de sculpture, but its reputation suffered as a result of public personnel issues. Abraham Bosse printmaker, and perspective instructor at the academy who had been close friends with the editors of the Trattato/Traitté was threatened by the loss of his teaching position in 1661. He retaliated by publishing an excerpt from a letter by Poussin alleging that his original drawings were ruined by Errard's additions. Bosse republished the letter excerpt again with a long list of errors in the text. The book nevertheless continued to be referenced and admired by important writers such as André Félibien and Roger de Piles However, in the 18th century Pierre-François Giffart, who published the first pocket edition of the Traité de la peinture in 1716 (lot 553), decided to cut costs by reducing the drawings of human figures to line engravings without shading or settings. This had a significant impact on the reception of the volume as rumors spread that Errard had ruined Poussin's drawings by adding shading. Both Jean Paul Rigaud, translator of the English 1802 edition, and Gault de Saint Germain, editor of the 1803 Traité, believed Poussin's originals were line drawings all'antica.

This manuscript, as well as the copy now in the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York (MA 23865; Bibliotheca Brookeriana I, 11 October 2023, lot 56) provide evidence of how numerous French artists and writers gained knowledge of the contents of the added chapters and their drawings.

In conclusion, the manuscript offered for sale has considerable historical importance. Its five parts testify to crucial stages in the publication process including Dal Pozzo's efforts to establish an accurate text, to expand the contents to include Leonardo's autograph writings on painting, to document their history, and to provide engravings for a modern publication worthy of the fame of Leonardo da Vinci

Works Cited:Barone, Juliana. “Poussin as Engineer of the Human Figure: The Illustrations for Leonardo’s Trattato.” In Re-Reading Leonardo, edited by Claire Farago, 197–235. Farnham: Ashgate, 2009.

Farago, Claire, Janis Bell, and Carlo Vecce. The Fabrication of Leonardo da Vinci’s Trattato della pittura with a scholarly edition of the editio princeps (1651) and an annotated English translation. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2018 (Brill’s Studies on Art, Art History, and Intellectual History, v. 18.)

Sparti, Donatella. “Cassiano dal Pozzo, Poussin and the Making and Publication of Leonardo’s ‘Trattato’.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 66 (2003): 143–88.

Steinitz, Kate Trauman. Leonardo da Vinci’s Trattato della Pittura. Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1958.

We are very grateful to Janis Bell and Pauline Maguire Robison for providing the above description of this manuscript and its genesis.

4to (239 x 170 mm, mount size; page size approx. 180/190 x 125/130 mm). 192 leaves, inset into blue paper frames: folios 1-115 are the main text, written in brown ink on both sides of the leaf, in two different hands, with a few diagrams; folios 116-125 are optical diagrams in pen and ink, with a few in black chalk, drawn on the recto only; folios 126-133 contain Alcune memorie de' fatti da Leonardo da Vinci .. del P.D. Gio Ambo. Mazzenta, written in brown ink on both sides of the leaf; folios 134-162 are optical diagrams and figure studies, in pen and ink and wash, drawn on the recto only. (Some ink corrosion resulting in holes, a few leaves starting to detach from the mount, other occasional light staining or browning.)

binding: Remboîtage of seventeenth-century French red morocco gilt (253 x 183 mm), plausibly by the Atelier "Rocolet", covers elaborately gilt with a pointillé design and the arms of Matthieu Molé, seigneur de Champlâtreux [Olivier 258 fer 2], spine gilt with the original title erased from second compartment, gilt edges; the volume presumed to have been assembled in the early eighteenth century. (Binding slightly rubbed, joints cracking, a few small wormholes.)

provenance: Jacques Gabriel Huquier (1695-1772, artist and printmaker), sale, Paris, F.C. Joullain fils, 9 November 1772, lot 637 ("Copie en Italien du Manuscrit original sur la peinture, par Leonard de Vinci, avec les figures de la main de N. Poussin..."), fr. 30 — Antoine-Auguste Renouard (1765-1853), booklabel, sale, Paris, 20 November 1854, lot 605 (claiming that some of the manuscript is in the hand of Poussin's brother-in-law Gaspar Duguest), fr. 350, to — Adolphe Narcisse, comte de Thibaudeau (1795-1856, art collector), sale, Paris, 20 April 1857, lot 823, fr. 165 — Ambroise Firmin-Didot-(1790-1876), red gilt booklabel, sale, Paris, 12 June 1882, lot 44 — Martine, Comtesse de Béhague (1870-1939), by descent to — Marquis Hubert de Ganay (1922-1974), HH booklabel, sale, Sotheby's, Monaco, 1 December 1989, lot 70 — Georgette Barbara (Dodie) Naify Rosekrans (1919-2010), sale, Sotheby's, New York, Old Master Drawings, 25 January 2012, lot 25. acquisition: Purchased at the preceding sale.

Leonardo da Vinci Trattato della pittura. Manuscript on paper. [Rome: workshop of Cassiano dal Pozzo, ca 1633-1639]

Unique among the prepublication copies of Leonardo's Trattato della pittura, this manuscript in the Brooker collection is the only copy that contains the small sketches known as Urbinate drawings and copies of Poussin's illustrations. The Brooker manuscript is classified as C,2 in Kate Trauman Steinitz's essential catalogue, Leonardo da Vinci's Trattato della pittura (Copenhagen 1958, pages 80-82). It appears as C1 in the classification of nearly fifty pre-publication manuscripts on the website dedicated to the Treatise on Painting. The University of Virginia (Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities) maintains the website, which is accessible via www.treatiseonpainting.org.

Steinitz traced the manuscript's history back to the early 18th century. Before its current owner, the Brooker manuscript belonged to the Marquis Hubert de Ganay, who inherited it from his aunt, the Comtesse de Béhague (Béarn). Before that, the manuscript passed through the hands of several individuals, including Huquier, Antoine-Auguste Renouard, Count Thibaudeau, and Ambroise Firmin-Didot- Recent research casts doubt on Steinitz's supposition (based on notes by Renouard) that Roland Fréart de Chambray used the Brooker manuscript, and that Nicolas Poussin formerly owned it.

The manuscript is bound in a striking red morocco leather binding embossed with the arms of Monsieur de Champlâtreux, son of Chancellor Matthieu Molé, President of the French parliament. Steinitz used this detail to date the binding to before 1656, the year Molé died. However, further research has revealed that the binding was reused from another volume entitled Nouvelles observations et coniectures sur l'iris by Marin Cureau de la Chambre (Paris: Jacques Langlois 1651). T. Kimball Brooker has suggested that the binding dates from the 18th century, as indicated by the disparity between the size of the book block and the binding, traces of the former title "SUR/L'IRIS" on the spine, the marbled endpapers, and the window mounting of text and image on grey paper.

The date of the manuscript is significantly earlier. It divides into five parts: [1] Trattato text and sketches; [2] added chapters; [3] Mazenta's memoir; [4] checklist of chapter titles; [5] copies of illustrations to be used in the publication of the Trattato. The original documents, from which the copies in the Brooker manuscript derive, belonged to Cassiano dal Pozzo (1588-1657), a well-known collector and bibliophile, supporter of scientific research, early patron of Nicolas Poussin and a prominent influencer of culture in Rome during the pontificate of Pope Urban VIII. Internal evidence and comparison with other known copies from Dal Pozzo's atelier suggest that the manuscript offered for sale was started before 1633 and finished by 1639.

Dal Pozzo directed the project to publish Leonardo's writings under the auspices of Cardinal Francesco Barberini (1597-1679), nephew to Urban VIII. Dal Pozzo supported early modern science as a member of the select Accademia dei Lincei, a scientific society founded by Federico Cesi (1585-1630). Dal Pozzo helped edit Galileo's controversial text, The Assayer, and arranged funding for publications on the flora and fauna of the new world, for a volume on citrus fruits, and for many other texts on the natural world. He compiled a mega-collection of illustrated sheets of antiquities, inscriptions, flora, fauna, fossils, fungi, and other curiosities of nature known as the Museo Cartaceo (Paper Museum).

Dal Pozzo owned a copy of Leonardo's writings when he arrived in Rome from Florence in 1612 (unpublished research of Pauline Maguire). Around 1634, Dal Pozzo gave this copy (modern designation vb), now in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, to Cardinal Barberini for the Barberini Library. It bears the collocation Barb. Lat. 4304. Early in the publication project, Dal Pozzo compiled m3 (Biblioteca Ambrosiana MS H228 inf.), a text derived from a different source than vb's. He commissioned original drawings from Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665) and original diagrams from the scientific researcher and mathematician, Gaspare Berti (1601-1643), to be used for engravings in a lavish publication. Both vb and m3 were used to compile the manuscript offered for sale.

Part 1: Brooker (fols.1r-101r) is a copy of the text and sketches of Dal Pozzo's manuscript vb (BAV MS Barb. Lat. 4304). The corrections and supplemental text inserted in the margins and between lines of text derive from m3. Sparti (2003) incorrectly surmised that the annotations were by Trichet du Fresne, an attribution that cannot be sustained by handwriting comparisons nor by what we can firmly ascertain about the early date of this text. The copy from vb was probably executed before Dal Pozzo employed Poussin and Berti to illustrate the text of m3, which took place in 1633-1634. Dal Pozzo updated the manuscript with additions and corrections years before Trichet du Fresne became involved in the Trattato publication project. Thus, this copy was an important point of reference during the years in which Leonardo's Trattato took final form in Rome.

Cassiano dal Pozzo's publication project included an effort to expand the number of chapters. The Milanese cleric Ambrogio Mazenta was promoted to Vicar and transferred to Rome in 1635, at which time he informed Dal Pozzo of the presence of autograph Leonardo manuscripts in Milan in the collection of Galeazzo Arconati (1580-1649). He prepared a memoir of the history of the manuscripts, which the Mazenta family had owned between 1589 and 1608.

Part 3: Brooker (fols. 126r-132r) is a copy of Mazenta's memoir, the original of which is bound in m2 (Biblioteca Ambrosiana MS H 227 inf.).

Dal Pozzo engaged the cooperation of Arconati to extract passages relevant to painting from the autograph manuscripts as a favor to Cardinal Barberini in return for favors for his son, Luigi Maria, and other compatriots. By 1636, Arconati had donated the notebooks to the Ambrosiana, but maintained access to them. Arconati eventually sent to Rome four separate compilations of excerpts and a large volume on hydraulics, conserved in the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

Part 2: Brooker (fols. 102-115v) is a copy of the first compilation of excerpts (the so-called "added chapters") that Dal Pozzo received, the original of which is bound in m2. The corresponding images (fols. 116-125) are missing from the source manuscript (m2) but are found in two other copies, m4 (BAMi MS H229 inf.) and n1, the elegant copy in Naples known as the Codex Corazza.

The "added chapters" pertain to light and shade, plants, movement, and perspective. Their inclusion in this manuscript copy and in another that went to France indicate that Dal Pozzo hoped the French publication would support his intention to include all of Leonardo's known writings on painting. The French editors chose not to include this material. The Traitté de la peinture (lots 550-551) included only the chapters in m3. The co-published Italian edition (lot 552), edited by Raphael Trichet du Fresne, was expanded to include reprints of Leon Battista Alberti's Della pittura and Della scultura and Lives of Leonardo da Vinci and Leon Battista Alberti written by Du Fresne.

To ensure the accuracy of his m3 text, Dal Pozzo sent Arconati a list of chapters that he found "difficult to understand" and asked Arconati to check them against Leonardo's original writings and another copy of the Trattato in Milan, presumably the Codex Pinellianus, m1 (Biblioteca Ambrosiana D 467 inf.).

Part 4: Brooker (fols. 132r-133r) is a copy of the "checklist" of chapter headings from Dal Pozzo's m3.

Part 5: Brooker (fols. 134-162) contains pen and wash copies of fifty-three diagrams and figures prepared for m3. The size of the figure drawings conforms to Nicolas Poussin's originals and were most likely made by tracing or lucidare, as were other copies in the Poussin atelier. Barone (2009) found that Poussin designed all the figures to the same scale for ease of replication. While 20th-century connoisseurs determined that the drawings in m3 were Poussin's originals, 17th-century writers considered the copies made in his studio to be authentic. This is certainly one reason that the pages were mounted and bound together as a collector's item.

Plans to publish Leonardo's writings on painting moved to Paris between late 1640, when Poussin travelled there to work for Louis XIII, and 1644, when Urban VIII died. Paris was a prominent center for book publication. The Trattato played a special role in the plans of Cardinal Richelieu (1585-1642) and François Sublet de Noyers (1589-1645) to bring Italian culture to France. They employed French artists in Rome to make copies of famous paintings and plaster casts of antique statues to be used for the education of artists at their own academy of art. The publication was delayed until 1651 due to the deaths of Richelieu and King Louis XIII, the fall from grace of Sublet, and years of political turmoil during the regency period of Louis XIV, but a French académie de peinture et de sculpture was founded in 1648.

The publications in 1651 were initially a great success. Charles Errard (1606-1689), first painter to the king, supervised the volumes, preparing designs for the engravers to be used in the printed editions. He standardized the column width by adding fictive mats and frames around the diagrams and landscapes and adding landscape or architectural backgrounds to the figure drawings. He oversaw the challenging task of printing each page twice: once for the text on a relief press, again for the illustrations on an intaglio press — a difficult task requiring precise alignment at a time when printing technology lacked precision devices. Each printed copy varies slightly from others as a result. The quantity of paper reserved for the publication bearing the watermark of Richelieu turned out to be inadequate, with the result that some copies include sheets or quires with different paper.

The Traitté was adopted as an instructional text by the royal Académie de peinture et de sculpture, but its reputation suffered as a result of public personnel issues. Abraham Bosse printmaker, and perspective instructor at the academy who had been close friends with the editors of the Trattato/Traitté was threatened by the loss of his teaching position in 1661. He retaliated by publishing an excerpt from a letter by Poussin alleging that his original drawings were ruined by Errard's additions. Bosse republished the letter excerpt again with a long list of errors in the text. The book nevertheless continued to be referenced and admired by important writers such as André Félibien and Roger de Piles However, in the 18th century Pierre-François Giffart, who published the first pocket edition of the Traité de la peinture in 1716 (lot 553), decided to cut costs by reducing the drawings of human figures to line engravings without shading or settings. This had a significant impact on the reception of the volume as rumors spread that Errard had ruined Poussin's drawings by adding shading. Both Jean Paul Rigaud, translator of the English 1802 edition, and Gault de Saint Germain, editor of the 1803 Traité, believed Poussin's originals were line drawings all'antica.

This manuscript, as well as the copy now in the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York (MA 23865; Bibliotheca Brookeriana I, 11 October 2023, lot 56) provide evidence of how numerous French artists and writers gained knowledge of the contents of the added chapters and their drawings.

In conclusion, the manuscript offered for sale has considerable historical importance. Its five parts testify to crucial stages in the publication process including Dal Pozzo's efforts to establish an accurate text, to expand the contents to include Leonardo's autograph writings on painting, to document their history, and to provide engravings for a modern publication worthy of the fame of Leonardo da Vinci

Works Cited:Barone, Juliana. “Poussin as Engineer of the Human Figure: The Illustrations for Leonardo’s Trattato.” In Re-Reading Leonardo, edited by Claire Farago, 197–235. Farnham: Ashgate, 2009.

Farago, Claire, Janis Bell, and Carlo Vecce. The Fabrication of Leonardo da Vinci’s Trattato della pittura with a scholarly edition of the editio princeps (1651) and an annotated English translation. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2018 (Brill’s Studies on Art, Art History, and Intellectual History, v. 18.)

Sparti, Donatella. “Cassiano dal Pozzo, Poussin and the Making and Publication of Leonardo’s ‘Trattato’.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 66 (2003): 143–88.

Steinitz, Kate Trauman. Leonardo da Vinci’s Trattato della Pittura. Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1958.

We are very grateful to Janis Bell and Pauline Maguire Robison for providing the above description of this manuscript and its genesis.

4to (239 x 170 mm, mount size; page size approx. 180/190 x 125/130 mm). 192 leaves, inset into blue paper frames: folios 1-115 are the main text, written in brown ink on both sides of the leaf, in two different hands, with a few diagrams; folios 116-125 are optical diagrams in pen and ink, with a few in black chalk, drawn on the recto only; folios 126-133 contain Alcune memorie de' fatti da Leonardo da Vinci .. del P.D. Gio Ambo. Mazzenta, written in brown ink on both sides of the leaf; folios 134-162 are optical diagrams and figure studies, in pen and ink and wash, drawn on the recto only. (Some ink corrosion resulting in holes, a few leaves starting to detach from the mount, other occasional light staining or browning.)

binding: Remboîtage of seventeenth-century French red morocco gilt (253 x 183 mm), plausibly by the Atelier "Rocolet", covers elaborately gilt with a pointillé design and the arms of Matthieu Molé, seigneur de Champlâtreux [Olivier 258 fer 2], spine gilt with the original title erased from second compartment, gilt edges; the volume presumed to have been assembled in the early eighteenth century. (Binding slightly rubbed, joints cracking, a few small wormholes.)

provenance: Jacques Gabriel Huquier (1695-1772, artist and printmaker), sale, Paris, F.C. Joullain fils, 9 November 1772, lot 637 ("Copie en Italien du Manuscrit original sur la peinture, par Leonard de Vinci, avec les figures de la main de N. Poussin..."), fr. 30 — Antoine-Auguste Renouard (1765-1853), booklabel, sale, Paris, 20 November 1854, lot 605 (claiming that some of the manuscript is in the hand of Poussin's brother-in-law Gaspar Duguest), fr. 350, to — Adolphe Narcisse, comte de Thibaudeau (1795-1856, art collector), sale, Paris, 20 April 1857, lot 823, fr. 165 — Ambroise Firmin-Didot-(1790-1876), red gilt booklabel, sale, Paris, 12 June 1882, lot 44 — Martine, Comtesse de Béhague (1870-1939), by descent to — Marquis Hubert de Ganay (1922-1974), HH booklabel, sale, Sotheby's, Monaco, 1 December 1989, lot 70 — Georgette Barbara (Dodie) Naify Rosekrans (1919-2010), sale, Sotheby's, New York, Old Master Drawings, 25 January 2012, lot 25. acquisition: Purchased at the preceding sale.

Testen Sie LotSearch und seine Premium-Features 7 Tage - ohne Kosten!

Lassen Sie sich automatisch über neue Objekte in kommenden Auktionen benachrichtigen.

Suchauftrag anlegen