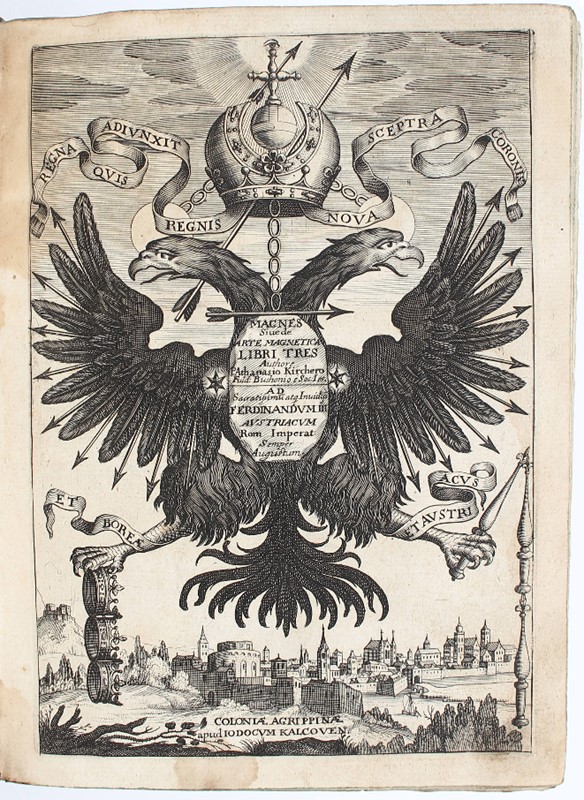

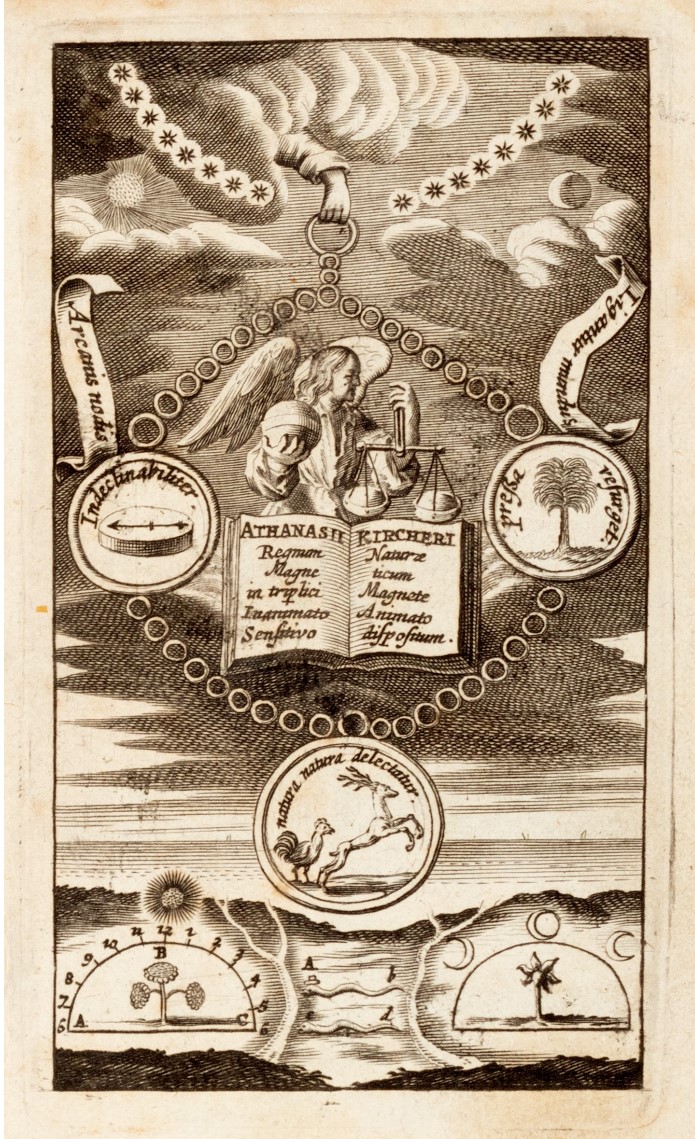

KIRCHER, Athanasius (1602-1680). Magnes sive de arte magnetica opus tripartitum. Cologne: Jodocus Kalcoven, 1643. Second edition of Kircher's remarkable compendium of magnetical lore, including the first use of the term electro-magnetism. "Kircher’s Magnes is filled with curiosities, both profound and frivolous. The work does not deal solely with what modern physicists call magnetism. Kircher discusses, for example, the magnetism of the earth and heavenly bodies; the tides; the attraction and repulsion in animals and plants; and the magnetic attraction of music and love. He also explains the practical applications of magnetism in medicine, hydraulics, and even in the construction of scientific instruments and toys. In the epilogue Kircher moves from the practical to the metaphysical—and Aristotelian—when he discusses the nature and position of God: 'the central magnet of the universe'" (Merrill). The beauty of its illustrations and the scope of its imagination earned this work admirers and it sold well—but had a mixed reception among Kircher's scientific contemporaries. Constantin Huygens called it "rather awful" and Evangelista Torricelli found it laughable—although he notes enjoying the section on the music which cures tarantula bites. Ironically, the Magnes also includes a section rebutting Kepler's theory of magnetism emanating from the sun and accusing the astronomer of "giving in too readily to his philosophical fantasies" (Linda Hall). Although its conclusions are perhaps occasionally dubious, it is a monumental example of Baroque book artistry as well as a testament to the international nature of Kircher's intellectual project. It is "the first work in which Kircher demonstrated his ability to create a global network of informants, using the combined resources of the Society of Jesus and the European-wide republic of letters to gather information" (Findlan). Both the Rome and Cologne editions are dedicated to the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III, and the contents of the two editions are the same apart from the privileges, which assign trans-Alpine rights to Kalcoven. The collation is complicated due to differences in the mounting of the volvelles and the fact that the full-page woodcuts are sometimes counted as plates; this copy is complete, and collates as both the Wolfenbüttel and BPL copies, with the volvelles unmounted. Merrill 5; Krivatsy 6399; Sommervogel IV, p 1048; see Norman 1215. See also William Ashworth, Jesuit Science in the Age of Galileo (Linda Hall Library, 1986) and Paul Findlan, "The Last Man Who Knew Everything … or Did He?" in Athanasius Kircher The Last Man Who Knew Everything (2004). Quarto (196 x 149mm). Engraved additional title, 29 engraved plates, woodcut diagrams throughout (some browning). Contemporary stiff yapped vellum, edges blue (lacking ties). Provenance: "Ex Libris Gentilis L'Achki" (stamp on rear board).

KIRCHER, Athanasius (1602-1680). Magnes sive de arte magnetica opus tripartitum. Cologne: Jodocus Kalcoven, 1643. Second edition of Kircher's remarkable compendium of magnetical lore, including the first use of the term electro-magnetism. "Kircher’s Magnes is filled with curiosities, both profound and frivolous. The work does not deal solely with what modern physicists call magnetism. Kircher discusses, for example, the magnetism of the earth and heavenly bodies; the tides; the attraction and repulsion in animals and plants; and the magnetic attraction of music and love. He also explains the practical applications of magnetism in medicine, hydraulics, and even in the construction of scientific instruments and toys. In the epilogue Kircher moves from the practical to the metaphysical—and Aristotelian—when he discusses the nature and position of God: 'the central magnet of the universe'" (Merrill). The beauty of its illustrations and the scope of its imagination earned this work admirers and it sold well—but had a mixed reception among Kircher's scientific contemporaries. Constantin Huygens called it "rather awful" and Evangelista Torricelli found it laughable—although he notes enjoying the section on the music which cures tarantula bites. Ironically, the Magnes also includes a section rebutting Kepler's theory of magnetism emanating from the sun and accusing the astronomer of "giving in too readily to his philosophical fantasies" (Linda Hall). Although its conclusions are perhaps occasionally dubious, it is a monumental example of Baroque book artistry as well as a testament to the international nature of Kircher's intellectual project. It is "the first work in which Kircher demonstrated his ability to create a global network of informants, using the combined resources of the Society of Jesus and the European-wide republic of letters to gather information" (Findlan). Both the Rome and Cologne editions are dedicated to the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand III, and the contents of the two editions are the same apart from the privileges, which assign trans-Alpine rights to Kalcoven. The collation is complicated due to differences in the mounting of the volvelles and the fact that the full-page woodcuts are sometimes counted as plates; this copy is complete, and collates as both the Wolfenbüttel and BPL copies, with the volvelles unmounted. Merrill 5; Krivatsy 6399; Sommervogel IV, p 1048; see Norman 1215. See also William Ashworth, Jesuit Science in the Age of Galileo (Linda Hall Library, 1986) and Paul Findlan, "The Last Man Who Knew Everything … or Did He?" in Athanasius Kircher The Last Man Who Knew Everything (2004). Quarto (196 x 149mm). Engraved additional title, 29 engraved plates, woodcut diagrams throughout (some browning). Contemporary stiff yapped vellum, edges blue (lacking ties). Provenance: "Ex Libris Gentilis L'Achki" (stamp on rear board).

.jpg)

Testen Sie LotSearch und seine Premium-Features 7 Tage - ohne Kosten!

Lassen Sie sich automatisch über neue Objekte in kommenden Auktionen benachrichtigen.

Suchauftrag anlegen