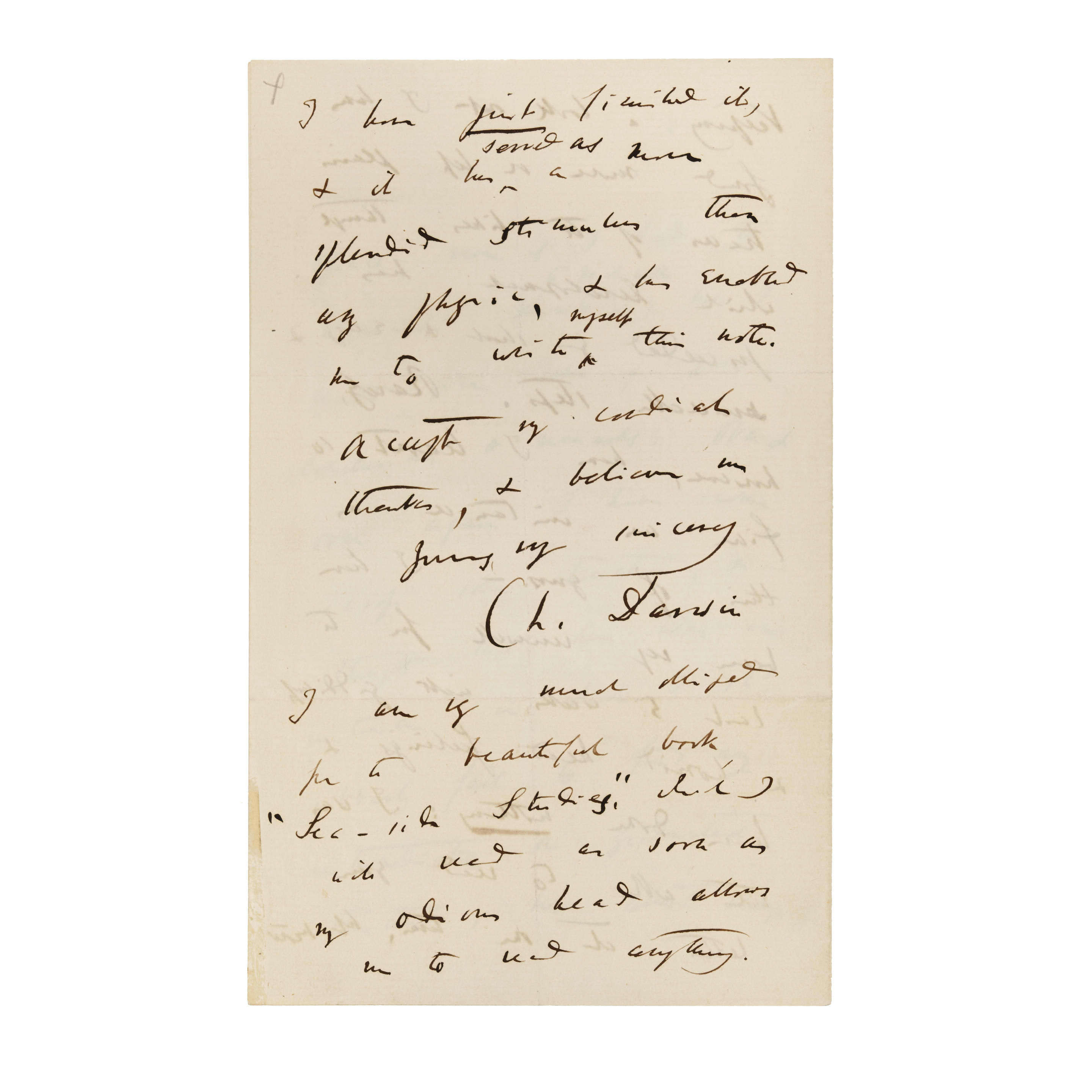

DARWIN, Charles Robert (1809-1882) Autograph letter signed (‘Ch. Darwin‘) to Alexander Agassiz, Down, Beckenham, Kent, 28 August [1871]. Four pages, 200 x 124mm, bifolium, on his personal stationery. "Almost always by keeping look out I have found more or less plain traces of the lines through which development has proceeded" Darwin writes on "gradation of structure," the phenomenon that informed his theory of natural selection, to the son of one of his opponents. A significant letter citing new information which he incorporated into the sixth and final edition of Origin in 1872. He opens with thanks for Agassiz’s letter of 9 August: "even if I had not wished much to learn something about the pediculariæ, would at any time have interested me beyond measure. It is a splendid case of gradation of structure […] Over & over again I have come across some structures, & thought that here was an instance in which I sh[oul]d utterly fail to find any intermediate or graduated structure; but almost always by keeping a look out I have found more or less plain traces of the lines through which development has proceeded by short & easy & serviceable steps. Rarely, however, have I learnt so fine an instance as this of yours." Darwin laments his recent "giddiness & horrid head feelings," which have left him unable to do anything for five weeks; he thanks Agassiz for a copy of his "beautiful" Seaside Studies, which he will read as soon as his "odious head" allows. To witness Darwin’s evolving understanding of the "gradation of structure" – the modifications observed within a species, genus or family that allow it to flourish under changing conditions of life – across the 1830s and 1840s is to see him reaching towards the theory of natural selection. Writing on the Galápagos finches – now better known as Darwin’s finches – in his Journals and Remarks for the first edition of The Voyage of the Beagle in 1839, Darwin remarked, drawing no conclusion, only: "It is very remarkable that a nearly perfect gradation of structure in this one group can be traced in the form of the beak, from one exceeding in dimensions that of the largest gros-beak, to another differing but little from that of a warbler." By 1845, when the second edition of the Voyage was published, a paradigm shift had occurred in his understanding of the phenomenon; he wrote then that: "Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends." Clearly enough, in the intervening years the significance of this mechanism for his developing theory of natural selection had become apparent — in later years, the phenomenon continued to be a source of wonder and to inform his thinking and writing. Here, Darwin writes to Alexander Agassiz (1835-1910; zoologist and engineer), the son of a well-known critic of his theory of evolution, Louis Agassiz, to thank him for his observations on gradation of structure in the invertebrate marine genus Pedicularis. Darwin’s keen interest in these marine invertebrates should be understood in the context of his own intellectual development: he began his studies in biology as a teenager focusing on local marine life and produced four large volumes in this field in the 1850s, empirical scientific research which is thought to have provided indubitable evidence of the theory of evolution to Darwin’s mind. Darwin incorporated Agassiz’s observations into his sixth and final edition of the Origin, published just a few months later, in 1872. He devoted four paragraphs to Agassiz's studies (pp. 191-193), concluding: "I wish I had space here to give a fuller abstract of Mr. Agassiz's interesting observations on the development of the pedicellaria." DCP-LETT-7918G. Alexander Agassiz (1835–1910), was a marine zoologist and the son of the Swiss-born American biologist Louis Agassiz, who was on

DARWIN, Charles Robert (1809-1882) Autograph letter signed (‘Ch. Darwin‘) to Alexander Agassiz, Down, Beckenham, Kent, 28 August [1871]. Four pages, 200 x 124mm, bifolium, on his personal stationery. "Almost always by keeping look out I have found more or less plain traces of the lines through which development has proceeded" Darwin writes on "gradation of structure," the phenomenon that informed his theory of natural selection, to the son of one of his opponents. A significant letter citing new information which he incorporated into the sixth and final edition of Origin in 1872. He opens with thanks for Agassiz’s letter of 9 August: "even if I had not wished much to learn something about the pediculariæ, would at any time have interested me beyond measure. It is a splendid case of gradation of structure […] Over & over again I have come across some structures, & thought that here was an instance in which I sh[oul]d utterly fail to find any intermediate or graduated structure; but almost always by keeping a look out I have found more or less plain traces of the lines through which development has proceeded by short & easy & serviceable steps. Rarely, however, have I learnt so fine an instance as this of yours." Darwin laments his recent "giddiness & horrid head feelings," which have left him unable to do anything for five weeks; he thanks Agassiz for a copy of his "beautiful" Seaside Studies, which he will read as soon as his "odious head" allows. To witness Darwin’s evolving understanding of the "gradation of structure" – the modifications observed within a species, genus or family that allow it to flourish under changing conditions of life – across the 1830s and 1840s is to see him reaching towards the theory of natural selection. Writing on the Galápagos finches – now better known as Darwin’s finches – in his Journals and Remarks for the first edition of The Voyage of the Beagle in 1839, Darwin remarked, drawing no conclusion, only: "It is very remarkable that a nearly perfect gradation of structure in this one group can be traced in the form of the beak, from one exceeding in dimensions that of the largest gros-beak, to another differing but little from that of a warbler." By 1845, when the second edition of the Voyage was published, a paradigm shift had occurred in his understanding of the phenomenon; he wrote then that: "Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends." Clearly enough, in the intervening years the significance of this mechanism for his developing theory of natural selection had become apparent — in later years, the phenomenon continued to be a source of wonder and to inform his thinking and writing. Here, Darwin writes to Alexander Agassiz (1835-1910; zoologist and engineer), the son of a well-known critic of his theory of evolution, Louis Agassiz, to thank him for his observations on gradation of structure in the invertebrate marine genus Pedicularis. Darwin’s keen interest in these marine invertebrates should be understood in the context of his own intellectual development: he began his studies in biology as a teenager focusing on local marine life and produced four large volumes in this field in the 1850s, empirical scientific research which is thought to have provided indubitable evidence of the theory of evolution to Darwin’s mind. Darwin incorporated Agassiz’s observations into his sixth and final edition of the Origin, published just a few months later, in 1872. He devoted four paragraphs to Agassiz's studies (pp. 191-193), concluding: "I wish I had space here to give a fuller abstract of Mr. Agassiz's interesting observations on the development of the pedicellaria." DCP-LETT-7918G. Alexander Agassiz (1835–1910), was a marine zoologist and the son of the Swiss-born American biologist Louis Agassiz, who was on

.jpg)

Testen Sie LotSearch und seine Premium-Features 7 Tage - ohne Kosten!

Lassen Sie sich automatisch über neue Objekte in kommenden Auktionen benachrichtigen.

Suchauftrag anlegen