Paul Wittgenstein

THE MUSIC ARCHIVE AND LIBRARY OF PAUL WITTGENSTEIN, comprising autograph manuscripts, printed and manuscript music

1. AUTOGRAPH AND SCRIBAL MANUSCRIPTS AND PRINTED SOURCES OF WORKS COMMISSIONED BY WITTGENSTEIN, MANY EXTENSIVELY ANNOTATED AND REVISED BY HIM:

Richard Strauss. Scribal sources for two works for piano left hand and orchestra, 5 archive boxes

PARERGON ZUR SINFONIA DOMESTICA, op.73 (1925) [Trenner 209a]

Manuscript piano arrangement by Otto Singer, with Wittgenstein’s alterations on endpapers, 42 pages, folio

Another copy, with differences and changes, revised keyboard part laid down over the original in places, with annotations by Wittgenstein, 40 pages, folio

Manuscript of the piano part, scribal hand, extensively annotated by Wittgenstein, including cuts and alterations, 32 pages

Manuscript set of orchestral parts, marked up, used at the first performances, “Dresden 16 Oktober 1925…Budapest 4 January 1926, Graz, 23 January 1926…22.3.1926 R. Strauss - Wittgenstein. Prag…Leipzig, January 1930 [etc.]…II. Probe R. Strauss anwesend!”, each signed by the copyist

Another set of manuscript orchestral parts, marked up; and four reproductions of the scribal score

PANATHENÄENZUG FOR PIANO LEFT HAND AND ORCHESTRA, op.74 (1926-1928) [Trenner 254]

Scribal manuscript full score marked up by a conductor (?Franz Schalk), detailing cuts and alterations and changes to the scoring, 129 pages, folio

Scribal arrangement for two pianos, the score being Wittgenstein’s performing manuscript of the solo part, with fingering and alterations by him in pencil, 115 pages, folio

Two marked-up sets of manuscript orchestral parts

Franz Schmidt. Collection of autograph manuscripts etc., 5 archive boxes

PIANO CONCERTO IN E FLAT

Autograph full score, 126 pages, folio, dated at the end by Schmidt, Perchtoldsdorf 18 October 1934

Partly autograph manuscript arranged for two pianos (autograph from p.53), annotated by Wittgenstein, 78 pages, folio

Set of manuscript instrumental parts, scribal hand; autograph piano part, annotated by Wittgenstein

PIANO QUINTET FOR PIANO LEFT HAND, TWO VIOLINS, VIOLA AND VIOLONCELLO, IN G MAJOR

Autograph manuscript score, marked up by Wittgenstein, 102 pages, dated Hartberg, 14 August 1926, together with, loosely inserted, an autograph cadenza, 7 pages

Six sets of manuscript parts, 24 volumes in all

CLARINET QUINTET FOR PIANO (LEFT HAND), CLARINET IN A, VIOLIN, VIOLA AND VIOLONCELLO

Autograph score, dated at end Perchtoldsdorf, 30 June 1938, annotated by Wittgenstein, 127 pages, folio

Set of manuscript parts

2ND CLARINET QUINTET FOR PIANO (LEFT HAND), CLARINET IN B FLAT, VIOLIN, VIOLA AND VIOLONCELLO

Scribal score, annotated throughout by Wittgenstein, 84 pages, folio, 1932; another scribal score, dated 1933 at the end by the scribe

Two sets of manuscript parts

TOCCATA FOR PIANO (OR HARPSICHORD)

Autograph manuscript, heavily annotated by Wittgenstein, 7 pages, folio, 1938

VARIATIONS ON A THEME OF BEETHOVEN FOR PIANO (LEFT HAND) AND ORCHESTRA

Autograph full score, marked for performance by the conductor, 67 pages, Hartberg, 22 August 1923

Autograph manuscript of the score for two pianos, marked up by Wittgenstein, some revised passages pasted over, 49 pages, folio, dated at the end, Hartberg, 22 August 1923

Autograph keyboard part, annotated by Wittgenstein, 21 pages, folio, incomplete, lacking the final movement

Instrumental scribal parts, marked up for the early performances, 42 volumes, including duplicates

Maurice Ravel

PIANO CONCERTO FOR THE LEFT HAND. Collection of manuscript and printed scores and parts, 4 archive boxes

Manuscript full score, marked up by a conductor, 87 pages, folio

Another copy, similarly marked, 87 pages, folio (“Als Manuskript gedruckt”), Vienna: Kugel, 1931

Photographic reproduction of a scribal manuscript, for two pianos, marked up and revised by Wittgenstein, whole passages removed or replaced, with timing (18-19 minutes), 48 pages, folio

Manuscript set of orchestral parts, marked up, several sets (2 boxes)

First edition of the full score, marked up by a conductor

Another copy, signed with initials “P.W.”, marked throughout by a conductor

Printed set of parts, marked by a conductor

Four photographic reproductions of the first edition, marked up

Sergei Prokofiev

FOURTH PIANO CONCERTO

Manuscript full score, 115 pages, folio; in an archive box, together with:

Benjamin Britten

DIVERSIONS ON A THEME

Set of marked-up orchestral parts, photo-reproduction, c.100 pages

Erich Wolfgang Korngold. Manuscripts of two works for piano left-hand, 3 archive boxes

PIANO CONCERTO IN C SHARP MINOR, op.17

Manuscript full score, scribal hand, some annotations in pencil by Korngold, marked up by the conductor (Korngold?), some considerable alterations and revisions to the orchestration in pencil, 97 pages, very large folio, 36-stave paper, unboxed, Vienna, April 1925

Another copy, the work apparently in an earlier state, with many pasted-over changes, undated, 114 pages, folio

Manuscript orchestral parts, copyists’ hands, marked up for performance, many changes and alterations, a number pasted over, autograph pastedown by Korngold (violin II, fig.78); lists of performances and players at the end of several parts, including for the first performance, in April 1925

Manuscript piano part, extensively annotated by Wittgenstein, some alterations on additional leaves, 114 pages, folio

Another copy, marked “Begleitung”, 118 pages, folio

Full score, first edition, large folio, 3 copies, not boxedSUITE FOR TWO VIOLINS, VIOLONCELLO AND PIANO LEFT HAND

Four sets of parts, marked up for performance, comprising one including score with piano part, heavily marked up by Wittgenstein in pencil, with timings, and three other sets of parts for violins and violoncello

Alexander Tansman. Concert Piece for Piano, autograph manuscript (transparencies) and 11 spiral-bound photo-reproduced scores, reproduction orchestral parts, and a 2-part piano arrangement, the piano part extensively rewritten by Wittgenstein, many hundreds of pages [1943], in 2 archive boxes

Serge Bortkiewicz

Manuscript of the 2nd Piano Concerto, full score, scribal hand, 137 pages, folio

Autograph manuscript of the Concert-Fantasie, reduction for two pianos, heavily annotated by Wittgenstein, 62 pages, folio

Autograph manuscripts of two Etudes, Nocturne and Gavotte-Caprice for piano left hand, 20 pages, folio

Eduard Schütt. Paraphrase, for piano left hand and orchestra, autograph full score, instrumental parts, autograph two-part piano arrangement, extensively revised by Wittgenstein, several hundred pages as well as autograph manuscripts, parts etc. including by Godowsky, Szymonowicz, Walter Bricht, Ernest Walker (Variations on an Original Theme), Norman Demuth, Rudolf Braun (Piano Concerto), Gal, Hurtig, Grüters, 5 archive boxes 2. PAUL WITTGENSTEIN’S WORKING MANUSCRIPTS OF STUDIES ETC. FOR THE LEFT HAND, 4 archive boxes and one calf-backed folding box

Over 25 notebooks and albums containing compositions, technical exercises, studies for the left hand, transcriptions of music for piano left hand, trial fingerings for works by Bach, Ravel, Chopin, Schumann and Cramer, together with many thousands of pages of transcriptions of music for piano left hand, written in a scribal hand, but with annotations by Wittgenstein

Over 1300 volumes of printed music, including some stored in 29 archival boxes, most annotated by Wittgenstein, a considerable number signed with his right hand, many antiquarian items, some eighteenth and early nineteenth-century scores, with first and early editions of music by Brahms, Liszt, Mendelssohn, his teacher Leschetizky, Chopin, Berlioz, Schumann, Mahler, Loewe, Richard Strauss, Korngold, Stravinsky, Beethoven, Bach, Mozart, Haydn and many others; an interesting and large collection of first editions etc. of Czerny, John Field, Spohr, Thalberg, Clara Schumann, Hummel, Dreyschock, Simon Sechter, Cortot, Isidor Philipp; a large and varied number dealing with schools of piano virtuosity from Czerny to Cortot, via Bulow, Godowsky and Schütt; an extensive collection of music for piano duet, including thousands of pages of manuscript transcriptions of music by Spohr, Lieder, operatic scores, early or first editions of Weber, Méhul, Gretry, Spontini, Meyerbeer, Donizetti, Schumann, Wagner, Richard Strauss and Pfitzner; many bound uniformly, with “Paul Wittgenstein” in gilt on upper cover; many with Jugendstil bookplate. Including original bindings and volumes bound for Wittgenstein (his name gilt-stamped to covers), together with unbound items (original wrappers) stored in acid-free archival sleeves

THIS IS A HIGHLY IMPORTANT ARCHIVE RELATING TO THE LIFE AND WORK OF PAUL WITTGENSTEIN (1887-1961), the pianist who commissioned many outstanding works for the piano left hand and who was a significant figure in the musical life of Austria and the United States of America in the middle years of the twentieth century.

Its importance as a source for music by Ravel, Richard Strauss, Prokofiev, Britten and especially Franz Schmidt, can hardly be overestimated. It is a largely unknown and unexplored archive of research material: it reveals a great deal about Wittgenstein's working methods, how he treated his commissions, how he performed the works, how he recomposed sections to his liking and how he always sought to expand the range of music for piano left hand. This archive documents the evolution of some of the great piano concertos and concertante works of the twentieth century, by Ravel, Strauss, Prokofiev and Britten, in particular. It contains early versions of these works, many of which differ from the texts that have been handed down to us. It sheds light on all sorts of other issues: the nature of musical patronage in modern times, on composer and commissioner, on his taste and indeed on the wider activities of Wittgenstein and his important and interesting family. One aspect shines through: the bravery, the indomitable spirit and sheer stubbornness of Paul Wittgenstein who, through his indefatigable energy and persistence, carved out his own quite distinctive niche in the history of twentieth-century music and is responsible for some of its great masterpieces.

Paul was the seventh of the eight children of Karl Wittgenstein, the industrialist and steel manufacturer, one of the richest and most dynamic businessmen in the Habsburg empire. The family was a cultural powerhouse of creativity, commissioning works of art or creating them themselves. There was hardly an artist or composer in Vienna with whom the Wittgensteins were not acquainted. Karl was a self-made man and he expected great things of his five sons, three of whom committed suicide in their twenties. Only Ludwig, the great philosopher, and Paul lived to full maturity, both making a lasting impression on the world, though in quite different ways.

All of the Wittgenstein children were musical. Within the family, Paul's considerable talents were often taken for granted, and he was not regarded as anything special in comparison with other siblings. Yet he was the only member of the family to make a successful career as a musician. His training, befitting a Wittgenstein, was superb, studying with Malvine Bree and Theodore Leschetizky, himself a pupil of Czerny. Much of the music owned by Wittgenstein from his student years survives in the archive, together with his notes. Clearly, he was schooled as a virtuoso in the Liszt tradition, a style of performance that did not find favour within his family, who regarded him as too flashy and lacking in taste.

He made his debut in 1913, at the comparatively late age of 26, and was all set for a career as a concert virtuoso. Then, disaster struck. At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Wittgenstein was wounded while serving on the Russian Front and lost his right arm. He was captured and imprisoned for nearly two years, before being repatriated in 1916. From then on he re-created himself as a one-armed pianist, re-learning and re-forming his technique with a single-mindedness which would surely have impressed his hard-driven father, had he still been living. So successful was the transformation that he was able to cope with pianistic difficulties which would have challenged performers with two hands.

But it was not just his own technique and career that Wittgenstein had to remake: he had to create a repertory. Before Wittgenstein, very few musicians had written music for one hand: there are some small works by Brahms, Saint-Säens and Scriabin, but little of consequence. Wittgenstein at first created a repertoire by himself, adapting works by earlier composers, including several Lieder ohne Worte by Mendelssohn, arias by Mozart and even an operatic paraphrase by Liszt. Wittgenstein's work on these and on other projects is evident in the many manuscripts in the archive.

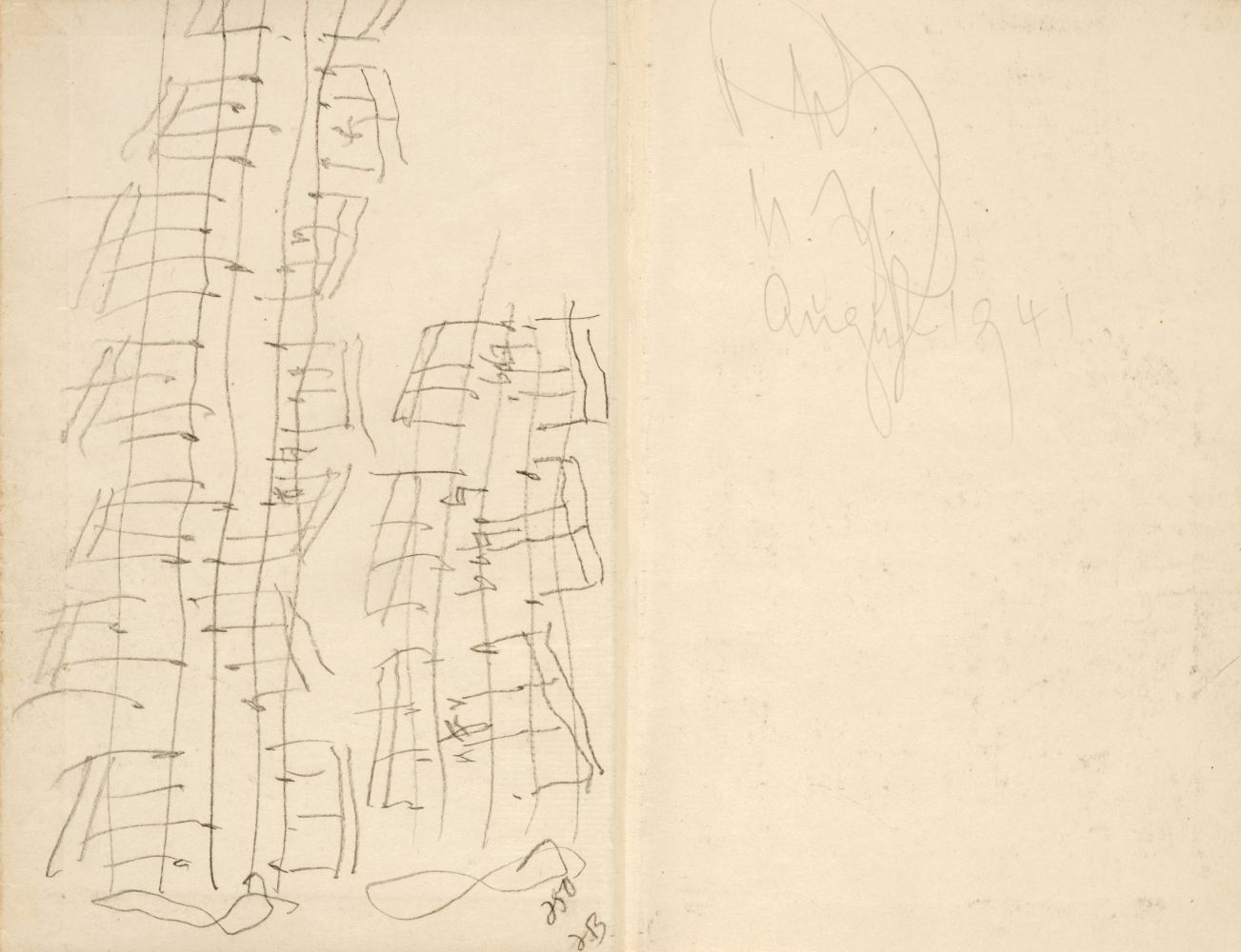

As the collection movingly shows, Wittgenstein was never particularly fluent at writing with his left hand. His interventions on music paper are over-size and dramatic, the ungainly, tottering and uneven lettering, and florid, chaotic musical notation, embody Wittgenstein's struggles. His determination to write down his thoughts, to test the fingering of a passage, or to create a personal and meaningful form of musical expression are at once impressive and moving.

A piano performer in the late-nineteenth-century tradition needed to have a few concertos in his repertoire and these were beyond Wittgenstein's own limited composing abilities. Harnessing his considerable financial inheritance and independence with his unremitting and almost ruthless determination, Wittgenstein commissioned a concerto repertory from a number of contemporary composers, creating, at the same time, a new form of patronage. In former centuries, a patron might commission a musician to produce musical works for his court. In only a few cases, such as with Frederick the Great, would the maecenas expect to play the music himself. But rarely would the commissioner have expected to have sole rights to the music and never that his own career as a performer should depend on it. This had perhaps unenvisaged consequences for composer, work and performer.

Wittgenstein commissioned more than twenty pieces of orchestral and chamber music from a variety of composers of different nationalities from the 1920s to the 1940s. The archive contains manuscripts or performing materials for almost all of these compositions. In 1938, the political situation required Wittgenstein to leave Vienna to live in New York. He left, taking his musical library with him and resumed his concert career and his commissioning activities in the United States.

The terms of Wittgenstein's beneficence were generous, but he was demanding. He held exclusive rights over performance for at least ten years; and in a number of cases, he published the music under his own auspices, also retaining the rights. At the end of concerts, the manuscript parts and conductors' score were collected and returned to Wittgenstein, whose exclusivity in most cases precluded performance by anyone else. This means that the surviving conductor's scores must contain valuable performance information, possibly in the hands as such great interpreters as Bruno Walter and Franz Schalk.This is an invaluable and almost unique resource.

Even a successful and well-established composer such as Richard Strauss agreed to such terms. This gave WIttgenstein great control over a work, particularly if he did not like the finished result. Some major pieces such as Prokofiev's Fourth Piano Concerto were neither performed nor published in the composer's lifetime, to the detriment of the work and author. Richard Strauss's two works, the Parergon zur Symphonia Domestica and the Panathenäenzug (see lots 000 and 000), were first published in Wittgestein's edition. With the performer's exclusive rights to performance and publication, this did not allow these two interesting pieces to enter the repertoire. Ravel, whose Piano Concerto for the left hand is the one supreme masterpiece in the collection, seems not to have allowed himself to be constrained by Wittgenstein's publishing requirement (Durand in Paris printed the score), and nor was he so much inhibited by the exclusivity of performance. However, this did not stop Wittgenstein from having Ravel's delicate and extraordinary orchestral score arranged for military band in a wartime performance in Philadelphia in 1943, the composer no doubt spinning in his grave.

The survival of so many performing versions of Wittgenstein's commissions in the archive allows the opportunity to compare the progress of different compositions during their early years in the concert repertory and the changes wrought by Wittgenstein. This is especially so with the composer who really flourished under Wittgenstein's patronage, the Austrian, Franz Schmidt. A cellist and pupil of Bruckner and Leschetizky, a composer of Romantic sensibility and finely crafted, if expansive, music, Schmidt was only peripherally influenced by the more advanced developments of his contemporaries.The archive contains autograph material for six major compositions, including the Piano Concerto, three chamber quintets and a set of concertante variations on a theme of Beethoven.This is a substantial proportion of Schmidt's output and demonstrates the importance of Wittgenstein on his career as a composer. The pianist clearly stipulated what he wanted from Schmidt and was pleased with the results. For example, the long piano cadenza in the Quintet with strings was added later and at the pianist's behest. To judge by the number of manuscripts, the piano concerto reached its final form through several versions and many vicissitudes. The Toccata contains many revisions and rewrites by Wittgenstein.

Schmidt was held up to Britten and others by Wittgenstein as a model composer. The Englishman did not have much sympathy with Schmidt's music when Wittgenstein sent him his scores. With Richard Strauss, Wittgenstein was on surer ground, but it is interesting to see how free was the pianist with Strauss's music. The scores and the instrumental parts here contain many changes and alterations made by Wittgenstein and his conductors, involving altered piano parts and figuration, changes to the scoring, and sometimes quite radical excisions and revisions. Wittgenstein's changes were not on the whole incorporated in the texts that have come down to us. These manuscripts are therefore highly important documents in the Receptionsgeschichte of a number of eminent works.

There is a strange irony in Wittgenstein's approach towards the younger composers, especially Prokofiev and Britten (though the older Ravel did not escape censure). By the 1930s, these composers had all moved away from the Romantic gestures which Wittgenstein loved. Neo-classical conciseness, almost the antithesis of Romanticism, pervades their scores. If Wittgenstein had hoped for a romantic concerto, he came to the wrong composers. He disdained the Prokofiev, played the Ravel many times, as can be judged also from the many copies of this work in the collection and the large number of instrumental parts, though professed to dislike it and seldom performed the Britten. Korngold was a composer who was more sympathetic, and his vast piano concerto exists in several different versions, often heavily annotated by Wittgenstein.

The large collection of instrumental parts for all these works are of great interest and importance. Not only are they marked up with all the alterations Wittgenstein and his conductors felt necessary, they also contain the details of interpretation of great conductors, such as Schalk and Bruno Walter, to name but two, who directed the premieres and early performances. Even more interesting are the comments of the musicians added at the end of many of the instrumental parts. These provide details of the earliest performances, the places and dates and sometimes comments as to who was there.

While the richness of the manuscript sources is perhaps the main highlight of the collection, it is not the sole reason for its importance. This lies of course in the evidence it provides for the musical development of a very singular man and artist, especially as revealed in the thousands of pages of Wittgenstein's own musical writings (some of which were used in his 1957 School for the Left Hand ) and the painstaking notes painfully produced by his left hand. And also in his library, showing the development of his musical education, his hard work and his love for the classics and byways of Romantic music which he so much admired.

LITERATURE:E.F. Flindell, 'Paul Wittgenstein (1887-1961): Patron and Pianist', The Music Review, xxxii (1971), p.10

Paul Wittgenstein

THE MUSIC ARCHIVE AND LIBRARY OF PAUL WITTGENSTEIN, comprising autograph manuscripts, printed and manuscript music

1. AUTOGRAPH AND SCRIBAL MANUSCRIPTS AND PRINTED SOURCES OF WORKS COMMISSIONED BY WITTGENSTEIN, MANY EXTENSIVELY ANNOTATED AND REVISED BY HIM:

Richard Strauss. Scribal sources for two works for piano left hand and orchestra, 5 archive boxes

PARERGON ZUR SINFONIA DOMESTICA, op.73 (1925) [Trenner 209a]

Manuscript piano arrangement by Otto Singer, with Wittgenstein’s alterations on endpapers, 42 pages, folio

Another copy, with differences and changes, revised keyboard part laid down over the original in places, with annotations by Wittgenstein, 40 pages, folio

Manuscript of the piano part, scribal hand, extensively annotated by Wittgenstein, including cuts and alterations, 32 pages

Manuscript set of orchestral parts, marked up, used at the first performances, “Dresden 16 Oktober 1925…Budapest 4 January 1926, Graz, 23 January 1926…22.3.1926 R. Strauss - Wittgenstein. Prag…Leipzig, January 1930 [etc.]…II. Probe R. Strauss anwesend!”, each signed by the copyist

Another set of manuscript orchestral parts, marked up; and four reproductions of the scribal score

PANATHENÄENZUG FOR PIANO LEFT HAND AND ORCHESTRA, op.74 (1926-1928) [Trenner 254]

Scribal manuscript full score marked up by a conductor (?Franz Schalk), detailing cuts and alterations and changes to the scoring, 129 pages, folio

Scribal arrangement for two pianos, the score being Wittgenstein’s performing manuscript of the solo part, with fingering and alterations by him in pencil, 115 pages, folio

Two marked-up sets of manuscript orchestral parts

Franz Schmidt. Collection of autograph manuscripts etc., 5 archive boxes

PIANO CONCERTO IN E FLAT

Autograph full score, 126 pages, folio, dated at the end by Schmidt, Perchtoldsdorf 18 October 1934

Partly autograph manuscript arranged for two pianos (autograph from p.53), annotated by Wittgenstein, 78 pages, folio

Set of manuscript instrumental parts, scribal hand; autograph piano part, annotated by Wittgenstein

PIANO QUINTET FOR PIANO LEFT HAND, TWO VIOLINS, VIOLA AND VIOLONCELLO, IN G MAJOR

Autograph manuscript score, marked up by Wittgenstein, 102 pages, dated Hartberg, 14 August 1926, together with, loosely inserted, an autograph cadenza, 7 pages

Six sets of manuscript parts, 24 volumes in all

CLARINET QUINTET FOR PIANO (LEFT HAND), CLARINET IN A, VIOLIN, VIOLA AND VIOLONCELLO

Autograph score, dated at end Perchtoldsdorf, 30 June 1938, annotated by Wittgenstein, 127 pages, folio

Set of manuscript parts

2ND CLARINET QUINTET FOR PIANO (LEFT HAND), CLARINET IN B FLAT, VIOLIN, VIOLA AND VIOLONCELLO

Scribal score, annotated throughout by Wittgenstein, 84 pages, folio, 1932; another scribal score, dated 1933 at the end by the scribe

Two sets of manuscript parts

TOCCATA FOR PIANO (OR HARPSICHORD)

Autograph manuscript, heavily annotated by Wittgenstein, 7 pages, folio, 1938

VARIATIONS ON A THEME OF BEETHOVEN FOR PIANO (LEFT HAND) AND ORCHESTRA

Autograph full score, marked for performance by the conductor, 67 pages, Hartberg, 22 August 1923

Autograph manuscript of the score for two pianos, marked up by Wittgenstein, some revised passages pasted over, 49 pages, folio, dated at the end, Hartberg, 22 August 1923

Autograph keyboard part, annotated by Wittgenstein, 21 pages, folio, incomplete, lacking the final movement

Instrumental scribal parts, marked up for the early performances, 42 volumes, including duplicates

Maurice Ravel

PIANO CONCERTO FOR THE LEFT HAND. Collection of manuscript and printed scores and parts, 4 archive boxes

Manuscript full score, marked up by a conductor, 87 pages, folio

Another copy, similarly marked, 87 pages, folio (“Als Manuskript gedruckt”), Vienna: Kugel, 1931

Photographic reproduction of a scribal manuscript, for two pianos, marked up and revised by Wittgenstein, whole passages removed or replaced, with timing (18-19 minutes), 48 pages, folio

Manuscript set of orchestral parts, marked up, several sets (2 boxes)

First edition of the full score, marked up by a conductor

Another copy, signed with initials “P.W.”, marked throughout by a conductor

Printed set of parts, marked by a conductor

Four photographic reproductions of the first edition, marked up

Sergei Prokofiev

FOURTH PIANO CONCERTO

Manuscript full score, 115 pages, folio; in an archive box, together with:

Benjamin Britten

DIVERSIONS ON A THEME

Set of marked-up orchestral parts, photo-reproduction, c.100 pages

Erich Wolfgang Korngold. Manuscripts of two works for piano left-hand, 3 archive boxes

PIANO CONCERTO IN C SHARP MINOR, op.17

Manuscript full score, scribal hand, some annotations in pencil by Korngold, marked up by the conductor (Korngold?), some considerable alterations and revisions to the orchestration in pencil, 97 pages, very large folio, 36-stave paper, unboxed, Vienna, April 1925

Another copy, the work apparently in an earlier state, with many pasted-over changes, undated, 114 pages, folio

Manuscript orchestral parts, copyists’ hands, marked up for performance, many changes and alterations, a number pasted over, autograph pastedown by Korngold (violin II, fig.78); lists of performances and players at the end of several parts, including for the first performance, in April 1925

Manuscript piano part, extensively annotated by Wittgenstein, some alterations on additional leaves, 114 pages, folio

Another copy, marked “Begleitung”, 118 pages, folio

Full score, first edition, large folio, 3 copies, not boxedSUITE FOR TWO VIOLINS, VIOLONCELLO AND PIANO LEFT HAND

Four sets of parts, marked up for performance, comprising one including score with piano part, heavily marked up by Wittgenstein in pencil, with timings, and three other sets of parts for violins and violoncello

Alexander Tansman. Concert Piece for Piano, autograph manuscript (transparencies) and 11 spiral-bound photo-reproduced scores, reproduction orchestral parts, and a 2-part piano arrangement, the piano part extensively rewritten by Wittgenstein, many hundreds of pages [1943], in 2 archive boxes

Serge Bortkiewicz

Manuscript of the 2nd Piano Concerto, full score, scribal hand, 137 pages, folio

Autograph manuscript of the Concert-Fantasie, reduction for two pianos, heavily annotated by Wittgenstein, 62 pages, folio

Autograph manuscripts of two Etudes, Nocturne and Gavotte-Caprice for piano left hand, 20 pages, folio

Eduard Schütt. Paraphrase, for piano left hand and orchestra, autograph full score, instrumental parts, autograph two-part piano arrangement, extensively revised by Wittgenstein, several hundred pages as well as autograph manuscripts, parts etc. including by Godowsky, Szymonowicz, Walter Bricht, Ernest Walker (Variations on an Original Theme), Norman Demuth, Rudolf Braun (Piano Concerto), Gal, Hurtig, Grüters, 5 archive boxes 2. PAUL WITTGENSTEIN’S WORKING MANUSCRIPTS OF STUDIES ETC. FOR THE LEFT HAND, 4 archive boxes and one calf-backed folding box

Over 25 notebooks and albums containing compositions, technical exercises, studies for the left hand, transcriptions of music for piano left hand, trial fingerings for works by Bach, Ravel, Chopin, Schumann and Cramer, together with many thousands of pages of transcriptions of music for piano left hand, written in a scribal hand, but with annotations by Wittgenstein

Over 1300 volumes of printed music, including some stored in 29 archival boxes, most annotated by Wittgenstein, a considerable number signed with his right hand, many antiquarian items, some eighteenth and early nineteenth-century scores, with first and early editions of music by Brahms, Liszt, Mendelssohn, his teacher Leschetizky, Chopin, Berlioz, Schumann, Mahler, Loewe, Richard Strauss, Korngold, Stravinsky, Beethoven, Bach, Mozart, Haydn and many others; an interesting and large collection of first editions etc. of Czerny, John Field, Spohr, Thalberg, Clara Schumann, Hummel, Dreyschock, Simon Sechter, Cortot, Isidor Philipp; a large and varied number dealing with schools of piano virtuosity from Czerny to Cortot, via Bulow, Godowsky and Schütt; an extensive collection of music for piano duet, including thousands of pages of manuscript transcriptions of music by Spohr, Lieder, operatic scores, early or first editions of Weber, Méhul, Gretry, Spontini, Meyerbeer, Donizetti, Schumann, Wagner, Richard Strauss and Pfitzner; many bound uniformly, with “Paul Wittgenstein” in gilt on upper cover; many with Jugendstil bookplate. Including original bindings and volumes bound for Wittgenstein (his name gilt-stamped to covers), together with unbound items (original wrappers) stored in acid-free archival sleeves

THIS IS A HIGHLY IMPORTANT ARCHIVE RELATING TO THE LIFE AND WORK OF PAUL WITTGENSTEIN (1887-1961), the pianist who commissioned many outstanding works for the piano left hand and who was a significant figure in the musical life of Austria and the United States of America in the middle years of the twentieth century.

Its importance as a source for music by Ravel, Richard Strauss, Prokofiev, Britten and especially Franz Schmidt, can hardly be overestimated. It is a largely unknown and unexplored archive of research material: it reveals a great deal about Wittgenstein's working methods, how he treated his commissions, how he performed the works, how he recomposed sections to his liking and how he always sought to expand the range of music for piano left hand. This archive documents the evolution of some of the great piano concertos and concertante works of the twentieth century, by Ravel, Strauss, Prokofiev and Britten, in particular. It contains early versions of these works, many of which differ from the texts that have been handed down to us. It sheds light on all sorts of other issues: the nature of musical patronage in modern times, on composer and commissioner, on his taste and indeed on the wider activities of Wittgenstein and his important and interesting family. One aspect shines through: the bravery, the indomitable spirit and sheer stubbornness of Paul Wittgenstein who, through his indefatigable energy and persistence, carved out his own quite distinctive niche in the history of twentieth-century music and is responsible for some of its great masterpieces.

Paul was the seventh of the eight children of Karl Wittgenstein, the industrialist and steel manufacturer, one of the richest and most dynamic businessmen in the Habsburg empire. The family was a cultural powerhouse of creativity, commissioning works of art or creating them themselves. There was hardly an artist or composer in Vienna with whom the Wittgensteins were not acquainted. Karl was a self-made man and he expected great things of his five sons, three of whom committed suicide in their twenties. Only Ludwig, the great philosopher, and Paul lived to full maturity, both making a lasting impression on the world, though in quite different ways.

All of the Wittgenstein children were musical. Within the family, Paul's considerable talents were often taken for granted, and he was not regarded as anything special in comparison with other siblings. Yet he was the only member of the family to make a successful career as a musician. His training, befitting a Wittgenstein, was superb, studying with Malvine Bree and Theodore Leschetizky, himself a pupil of Czerny. Much of the music owned by Wittgenstein from his student years survives in the archive, together with his notes. Clearly, he was schooled as a virtuoso in the Liszt tradition, a style of performance that did not find favour within his family, who regarded him as too flashy and lacking in taste.

He made his debut in 1913, at the comparatively late age of 26, and was all set for a career as a concert virtuoso. Then, disaster struck. At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Wittgenstein was wounded while serving on the Russian Front and lost his right arm. He was captured and imprisoned for nearly two years, before being repatriated in 1916. From then on he re-created himself as a one-armed pianist, re-learning and re-forming his technique with a single-mindedness which would surely have impressed his hard-driven father, had he still been living. So successful was the transformation that he was able to cope with pianistic difficulties which would have challenged performers with two hands.

But it was not just his own technique and career that Wittgenstein had to remake: he had to create a repertory. Before Wittgenstein, very few musicians had written music for one hand: there are some small works by Brahms, Saint-Säens and Scriabin, but little of consequence. Wittgenstein at first created a repertoire by himself, adapting works by earlier composers, including several Lieder ohne Worte by Mendelssohn, arias by Mozart and even an operatic paraphrase by Liszt. Wittgenstein's work on these and on other projects is evident in the many manuscripts in the archive.

As the collection movingly shows, Wittgenstein was never particularly fluent at writing with his left hand. His interventions on music paper are over-size and dramatic, the ungainly, tottering and uneven lettering, and florid, chaotic musical notation, embody Wittgenstein's struggles. His determination to write down his thoughts, to test the fingering of a passage, or to create a personal and meaningful form of musical expression are at once impressive and moving.

A piano performer in the late-nineteenth-century tradition needed to have a few concertos in his repertoire and these were beyond Wittgenstein's own limited composing abilities. Harnessing his considerable financial inheritance and independence with his unremitting and almost ruthless determination, Wittgenstein commissioned a concerto repertory from a number of contemporary composers, creating, at the same time, a new form of patronage. In former centuries, a patron might commission a musician to produce musical works for his court. In only a few cases, such as with Frederick the Great, would the maecenas expect to play the music himself. But rarely would the commissioner have expected to have sole rights to the music and never that his own career as a performer should depend on it. This had perhaps unenvisaged consequences for composer, work and performer.

Wittgenstein commissioned more than twenty pieces of orchestral and chamber music from a variety of composers of different nationalities from the 1920s to the 1940s. The archive contains manuscripts or performing materials for almost all of these compositions. In 1938, the political situation required Wittgenstein to leave Vienna to live in New York. He left, taking his musical library with him and resumed his concert career and his commissioning activities in the United States.

The terms of Wittgenstein's beneficence were generous, but he was demanding. He held exclusive rights over performance for at least ten years; and in a number of cases, he published the music under his own auspices, also retaining the rights. At the end of concerts, the manuscript parts and conductors' score were collected and returned to Wittgenstein, whose exclusivity in most cases precluded performance by anyone else. This means that the surviving conductor's scores must contain valuable performance information, possibly in the hands as such great interpreters as Bruno Walter and Franz Schalk.This is an invaluable and almost unique resource.

Even a successful and well-established composer such as Richard Strauss agreed to such terms. This gave WIttgenstein great control over a work, particularly if he did not like the finished result. Some major pieces such as Prokofiev's Fourth Piano Concerto were neither performed nor published in the composer's lifetime, to the detriment of the work and author. Richard Strauss's two works, the Parergon zur Symphonia Domestica and the Panathenäenzug (see lots 000 and 000), were first published in Wittgestein's edition. With the performer's exclusive rights to performance and publication, this did not allow these two interesting pieces to enter the repertoire. Ravel, whose Piano Concerto for the left hand is the one supreme masterpiece in the collection, seems not to have allowed himself to be constrained by Wittgenstein's publishing requirement (Durand in Paris printed the score), and nor was he so much inhibited by the exclusivity of performance. However, this did not stop Wittgenstein from having Ravel's delicate and extraordinary orchestral score arranged for military band in a wartime performance in Philadelphia in 1943, the composer no doubt spinning in his grave.

The survival of so many performing versions of Wittgenstein's commissions in the archive allows the opportunity to compare the progress of different compositions during their early years in the concert repertory and the changes wrought by Wittgenstein. This is especially so with the composer who really flourished under Wittgenstein's patronage, the Austrian, Franz Schmidt. A cellist and pupil of Bruckner and Leschetizky, a composer of Romantic sensibility and finely crafted, if expansive, music, Schmidt was only peripherally influenced by the more advanced developments of his contemporaries.The archive contains autograph material for six major compositions, including the Piano Concerto, three chamber quintets and a set of concertante variations on a theme of Beethoven.This is a substantial proportion of Schmidt's output and demonstrates the importance of Wittgenstein on his career as a composer. The pianist clearly stipulated what he wanted from Schmidt and was pleased with the results. For example, the long piano cadenza in the Quintet with strings was added later and at the pianist's behest. To judge by the number of manuscripts, the piano concerto reached its final form through several versions and many vicissitudes. The Toccata contains many revisions and rewrites by Wittgenstein.

Schmidt was held up to Britten and others by Wittgenstein as a model composer. The Englishman did not have much sympathy with Schmidt's music when Wittgenstein sent him his scores. With Richard Strauss, Wittgenstein was on surer ground, but it is interesting to see how free was the pianist with Strauss's music. The scores and the instrumental parts here contain many changes and alterations made by Wittgenstein and his conductors, involving altered piano parts and figuration, changes to the scoring, and sometimes quite radical excisions and revisions. Wittgenstein's changes were not on the whole incorporated in the texts that have come down to us. These manuscripts are therefore highly important documents in the Receptionsgeschichte of a number of eminent works.

There is a strange irony in Wittgenstein's approach towards the younger composers, especially Prokofiev and Britten (though the older Ravel did not escape censure). By the 1930s, these composers had all moved away from the Romantic gestures which Wittgenstein loved. Neo-classical conciseness, almost the antithesis of Romanticism, pervades their scores. If Wittgenstein had hoped for a romantic concerto, he came to the wrong composers. He disdained the Prokofiev, played the Ravel many times, as can be judged also from the many copies of this work in the collection and the large number of instrumental parts, though professed to dislike it and seldom performed the Britten. Korngold was a composer who was more sympathetic, and his vast piano concerto exists in several different versions, often heavily annotated by Wittgenstein.

The large collection of instrumental parts for all these works are of great interest and importance. Not only are they marked up with all the alterations Wittgenstein and his conductors felt necessary, they also contain the details of interpretation of great conductors, such as Schalk and Bruno Walter, to name but two, who directed the premieres and early performances. Even more interesting are the comments of the musicians added at the end of many of the instrumental parts. These provide details of the earliest performances, the places and dates and sometimes comments as to who was there.

While the richness of the manuscript sources is perhaps the main highlight of the collection, it is not the sole reason for its importance. This lies of course in the evidence it provides for the musical development of a very singular man and artist, especially as revealed in the thousands of pages of Wittgenstein's own musical writings (some of which were used in his 1957 School for the Left Hand ) and the painstaking notes painfully produced by his left hand. And also in his library, showing the development of his musical education, his hard work and his love for the classics and byways of Romantic music which he so much admired.

LITERATURE:E.F. Flindell, 'Paul Wittgenstein (1887-1961): Patron and Pianist', The Music Review, xxxii (1971), p.10

Testen Sie LotSearch und seine Premium-Features 7 Tage - ohne Kosten!

Lassen Sie sich automatisch über neue Objekte in kommenden Auktionen benachrichtigen.

Suchauftrag anlegen