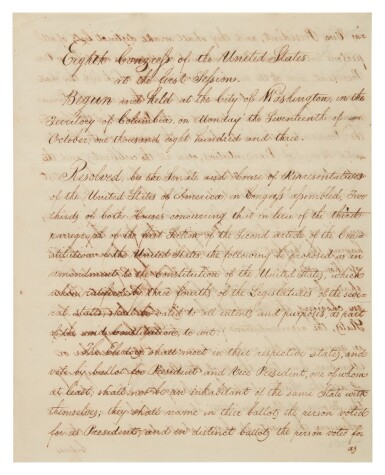

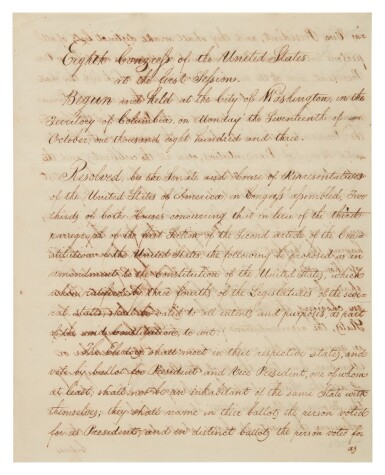

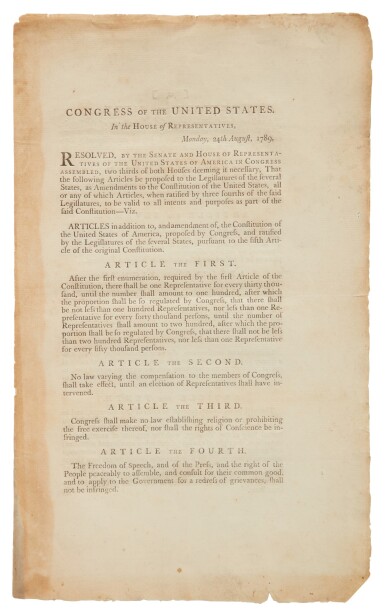

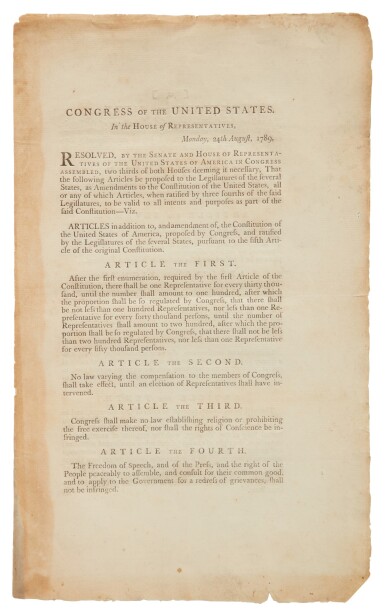

United States Constitution, Amendment XIIIThirty-Eighth Congress of the United States of America at the Second Session, Begun and Held at the City of Washington, on Monday, the Fifth day of December, One Thousand Eight Hundred and Sixty Four. A Resolution Submitting to the Legislatures of the Aeveral States A Proposition to Amend the Constitution of the United States. Resolved By The Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, Two Thirds of Both Houses Concurring, that the Following Article be Proposed to the Legislatures of the Several States As An Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which, when ratified by three-fourths of said Legislatures, shall be valid, to all intents and purposes, as a part of the said Constitution, namely:

Article XIII. Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction. Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

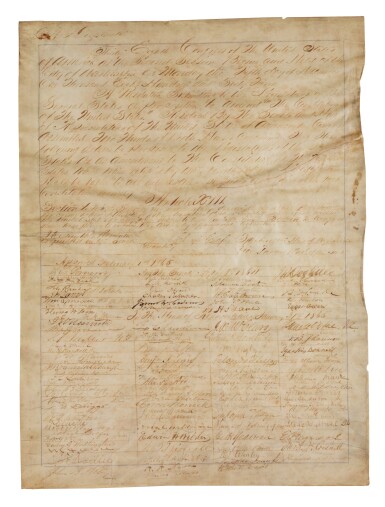

Engrossed document on vellum (532 x 395 mm, irregular), ruled in red and blue (now faint), marked at head "A Duplicate," Washington, D.C., ca. 1 February 1865, signed by Vice President Hannibal Hamlin, 31 Senators (all in the top 6 rows), 80 Representatives, and Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax (plus 5 duplicate signatures); lightly browned and soiled, some natural wrinkling, long tear (ca. 170 mm) at right margin into text, obscuring some text and artlessly repaired on verso.

The Emancipation Proclamation, by ushering in full abolition, helped fulfill the promise of the Declaration of Independence, rescuing the nation’s founding philosophy of human liberty from the charge of hypocrisy. As historians James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton note, the history of African Americans “both illustrates and contradicts the promise of America—the principles embodied in the nation’s founding documents” (Horton & Horton, In Hope of Liberty, ix).

While the Emancipation Proclamation was taking its effect in the field as the Union army advanced, Lincoln also advocated a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery everywhere in the United States. On 14 December 1863, Ohio Congressman James M. Ashley introduced such an amendment in the House of Representatives. Senator John Brooks Henderson of Missouri, a border state that still sanctioned slavery, followed suit on 11 January 1864, courageously submitting a joint resolution for an amendment abolishing slavery.

The proposal passed in the Senate on 8 April 1864, with a vote of 38 to 6. Two months later, however, it was defeated in the House of Representatives, 95 to 66 (or by another account, 93-65), shy of the 2/3 necessary for approval. Lincoln, not about to give up, made abolition a central plank of the National Union platform during his reelection campaign. He argued, “When the people in revolt, with a hundred days of explicit notice, that they could, within those days, resume their allegiance, without the overthrow of their institution, and that they could not so resume it afterwards, elected to stand out, such [an] amendment of the Constitution as [is] now proposed, became a fitting, and necessary conclusion to the final success of the Union cause. Such alone can meet and cover all cavils. …” (Basler, Collected Works, 7, 380).

But the outcome was in doubt until the final hour. A Pennsylvania Democrat, Archibald McAllister, opened the debate by explaining why he had changed his vote from a “Nay” to an “Aye.” He had been in favor of exhausting all means of conciliation, but was now satisfied that nothing short of independence would satisfy the Southern Confederacy, and that therefore it must be destroyed, and he must cast his vote against its cornerstone, and declare eternal war with the enemies of the country. Fellow Pennsylvania Democrat Alexander Hamilton Coffroth also changed his vote, and gave a speech advocating passage. Arguments continued until, finally, the votes were tallied. This time it passed, by a vote of 119 to 56, with eight abstentions. When Speaker Colfax declared the results, “a moment of silence succeeded, and then, from floor and galleries, burst a simultaneous shout of joy and triumph, spontaneous, irrepressible and uncontrollable, swelling and prolonged in one vast volume of reverberating thunder…” (Report of the special committee on the passage by the House of Representatives of the constitutional amendment for the abolition of slavery. January 31st, 1865: The Action of the Union League Club on the Amendment, February 9, 1865, in “From Slavery to Freedom.” American Memory, Library of Congress).

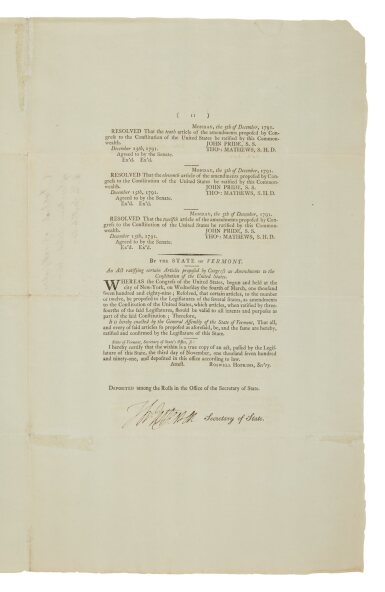

Having already been approved by the Senate the previous April, the amendment passed in the House on 31 January 1865. The engrossed manuscript was prepared, and Lincoln signed it on 1 February. There does not appear to be any record of the number of “souvenir” copies of the Amendment prepared for the legislators. Twelve to fifteen are known with Lincoln’s signature. Additional manuscript copies, like the present, are known signed by Senators, Congressmen and other officials, but with the space for the President’s name blank. On February 7th, the Senate, anxious not to set a precedent, resolved that the president’s signature had been “unnecessary” on a joint amendment resolution. The Senate secretary, John W. Forney, was directed to “withhold from the House of Representatives the message of the President informing the Senate that he had approved and signed the same” (Senate Journal).

The more notable signers of this copy, in addition to the vice president and speaker of the house, include John B. Henderson of Missouri, who had introduced the bill in the Senate; and James M. Ashley of Ohio, who introduced the bill in the House; Schuyler Colfax of Indiana, vice president under Grant; prominent abolitionists Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Charles Sumner of Massachusetts; and future presidential candidate James Blaine of Maine. Most of the amendment's support came from Republicans, but several Democrats helped secure its passage; the only two Democratic supporters in the Senate—Reverdy Johnson of Maryland and James Nesmith of Oregon —signed this copy, as did Ezra Wheeler of Wisconsin, who was the only Democrat to make a speech in favor of the amendment on the House floor. Also signing here is George Helm Yeaman of slave-holding Kentucky, who cast what proved to be the deciding vote. A complete list of signers is available upon request.

United States Constitution, Amendment XIIIThirty-Eighth Congress of the United States of America at the Second Session, Begun and Held at the City of Washington, on Monday, the Fifth day of December, One Thousand Eight Hundred and Sixty Four. A Resolution Submitting to the Legislatures of the Aeveral States A Proposition to Amend the Constitution of the United States. Resolved By The Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, Two Thirds of Both Houses Concurring, that the Following Article be Proposed to the Legislatures of the Several States As An Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which, when ratified by three-fourths of said Legislatures, shall be valid, to all intents and purposes, as a part of the said Constitution, namely:

Article XIII. Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction. Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Engrossed document on vellum (532 x 395 mm, irregular), ruled in red and blue (now faint), marked at head "A Duplicate," Washington, D.C., ca. 1 February 1865, signed by Vice President Hannibal Hamlin, 31 Senators (all in the top 6 rows), 80 Representatives, and Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax (plus 5 duplicate signatures); lightly browned and soiled, some natural wrinkling, long tear (ca. 170 mm) at right margin into text, obscuring some text and artlessly repaired on verso.

The Emancipation Proclamation, by ushering in full abolition, helped fulfill the promise of the Declaration of Independence, rescuing the nation’s founding philosophy of human liberty from the charge of hypocrisy. As historians James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton note, the history of African Americans “both illustrates and contradicts the promise of America—the principles embodied in the nation’s founding documents” (Horton & Horton, In Hope of Liberty, ix).

While the Emancipation Proclamation was taking its effect in the field as the Union army advanced, Lincoln also advocated a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery everywhere in the United States. On 14 December 1863, Ohio Congressman James M. Ashley introduced such an amendment in the House of Representatives. Senator John Brooks Henderson of Missouri, a border state that still sanctioned slavery, followed suit on 11 January 1864, courageously submitting a joint resolution for an amendment abolishing slavery.

The proposal passed in the Senate on 8 April 1864, with a vote of 38 to 6. Two months later, however, it was defeated in the House of Representatives, 95 to 66 (or by another account, 93-65), shy of the 2/3 necessary for approval. Lincoln, not about to give up, made abolition a central plank of the National Union platform during his reelection campaign. He argued, “When the people in revolt, with a hundred days of explicit notice, that they could, within those days, resume their allegiance, without the overthrow of their institution, and that they could not so resume it afterwards, elected to stand out, such [an] amendment of the Constitution as [is] now proposed, became a fitting, and necessary conclusion to the final success of the Union cause. Such alone can meet and cover all cavils. …” (Basler, Collected Works, 7, 380).

But the outcome was in doubt until the final hour. A Pennsylvania Democrat, Archibald McAllister, opened the debate by explaining why he had changed his vote from a “Nay” to an “Aye.” He had been in favor of exhausting all means of conciliation, but was now satisfied that nothing short of independence would satisfy the Southern Confederacy, and that therefore it must be destroyed, and he must cast his vote against its cornerstone, and declare eternal war with the enemies of the country. Fellow Pennsylvania Democrat Alexander Hamilton Coffroth also changed his vote, and gave a speech advocating passage. Arguments continued until, finally, the votes were tallied. This time it passed, by a vote of 119 to 56, with eight abstentions. When Speaker Colfax declared the results, “a moment of silence succeeded, and then, from floor and galleries, burst a simultaneous shout of joy and triumph, spontaneous, irrepressible and uncontrollable, swelling and prolonged in one vast volume of reverberating thunder…” (Report of the special committee on the passage by the House of Representatives of the constitutional amendment for the abolition of slavery. January 31st, 1865: The Action of the Union League Club on the Amendment, February 9, 1865, in “From Slavery to Freedom.” American Memory, Library of Congress).

Having already been approved by the Senate the previous April, the amendment passed in the House on 31 January 1865. The engrossed manuscript was prepared, and Lincoln signed it on 1 February. There does not appear to be any record of the number of “souvenir” copies of the Amendment prepared for the legislators. Twelve to fifteen are known with Lincoln’s signature. Additional manuscript copies, like the present, are known signed by Senators, Congressmen and other officials, but with the space for the President’s name blank. On February 7th, the Senate, anxious not to set a precedent, resolved that the president’s signature had been “unnecessary” on a joint amendment resolution. The Senate secretary, John W. Forney, was directed to “withhold from the House of Representatives the message of the President informing the Senate that he had approved and signed the same” (Senate Journal).

The more notable signers of this copy, in addition to the vice president and speaker of the house, include John B. Henderson of Missouri, who had introduced the bill in the Senate; and James M. Ashley of Ohio, who introduced the bill in the House; Schuyler Colfax of Indiana, vice president under Grant; prominent abolitionists Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Charles Sumner of Massachusetts; and future presidential candidate James Blaine of Maine. Most of the amendment's support came from Republicans, but several Democrats helped secure its passage; the only two Democratic supporters in the Senate—Reverdy Johnson of Maryland and James Nesmith of Oregon —signed this copy, as did Ezra Wheeler of Wisconsin, who was the only Democrat to make a speech in favor of the amendment on the House floor. Also signing here is George Helm Yeaman of slave-holding Kentucky, who cast what proved to be the deciding vote. A complete list of signers is available upon request.

.jpg)

Testen Sie LotSearch und seine Premium-Features 7 Tage - ohne Kosten!

Lassen Sie sich automatisch über neue Objekte in kommenden Auktionen benachrichtigen.

Suchauftrag anlegen